DEVELOPMENTS

Agriculture Finance with a Climate Lens Takes Off in Kenya

Aug 14, 2018

The effects of climate change in the already arid lands of Kenya are particularly tough on its economy. Think: tourism, arable agriculture, horticulture, floriculture, and livestock—all vulnerable to extreme changes in weather.

The U.K. Department for International Department (DFID) is known for approaching climate change in innovative ways. Its Hunger Safety Net Programme, for example, uses digital cash transfers to help the very poorest Kenyan households in times of drought and flood. Now, DFID is supporting a new path-breaking approach, the Finance Innovation for Climate Change Fund (FICCF), an initiative to promote the commercialization of climate-resilient commodities by on-lending to Kenyan smallholder farmers in the sorghum, cassava, dairy, and indigenous chicken value chains.

Launched in 2014 by the Strengthening Adaptation and Resilience to Climate Change in Kenya Plus (StARCK+) programme, the FICCF, implemented by DAI, will be run by the Kenya Markets Trust as StARCK+ winds down this month.

How Does the Fund Work?

Historically, Kenya’s financial institutions have been reluctant to lend to smallholder farmers. Not only has it been nearly impossible for small agribusinesses and farmers to get loans, but the financial institutions themselves had limited knowledge of the agriculture sector. The uncertainty brought on by climate change compounds the risky nature of lending to smallholder farmers.

Against this backdrop, the FICCF brings together a novel mix of partners that don’t typically work together: four microfinance institutions, 16 agribusiness aggregators, one climate information service provider, an insurance company, and an information and communications technology service provider, in addition to the technical and extension service providers contracted by the microfinance institutions to build farmer capacity through adaptive technologies and practices.

Working through the FICCF, these partners have created a mechanism where climate finance can flow through existing commercial financial institutions to smallholders and aggregators, while at the same time de-risking investments by providing hybrid insurance products and weather advisories. This combination of financial inclusion initiatives and market linkages within a climate lens is at the heart of the innovation.

The financial institutions market their services to smallholder farmers. Photo: DFID StARCK+.

The £2 million fund started as a pilot in 2014. To date, loans have been extended for such things as improved cow breeds, cow housing, fodder production, and seed for sorghum and cassava cuttings. The loans also enable aggregators to pay farmers promptly once they hand over their product, rather than have farmers waiting months until aggregators are paid by end buyers. So far, more than 5,000 farmers across 18 counties have received loans. When the long rainy season hits (March to June), the microfinance institutions provide loans for sorghum production and input financing. Another 4,000 farmers have taken advantage of the sorghum loans.

Appealing to the Banks and Farmers

To bring in the microfinance institutions, FICCF uses “returnable capital”—a revolving fund model to kickstart forward lending to aggregators and smallholders along the selected value chains. Returnable capital is essentially a pot of money that FICCF makes available to the microfinance institutions for three to four years; the institutions on-lend that money for six to 12 months, and when it is repaid the money is returned for further lending to farmers or aggregators.

In addition to loan financing, the FICCF offers microfinance institutions a 20 percent matching grant to fund technical assistance on climate-smart approaches for farmers.

Most FICCF clients are smallholders and small to medium-sized enterprises with no credit history, little collateral, and limited (although diverse) resources. Smallholders have only small areas of land for cropping and rearing, very low incomes, and limited access to inputs, assets, and infrastructure. Without irrigation or affordable water collection options, farmers rely on increasingly erratic seasonal rainfall. These limitations often make it difficult for farmers to subsist on what they cultivate or rear, and nearly impossible to produce enough to sell for income. FICCF’s financial inclusion model enables smallholders to access loans for farm inputs, with the goal of facilitating a transformational leap to a rural economy beyond subsistence.

Increased productivity at the farm translates into overall improved livelihoods, a greater ability to borrow and invest. Ann Maina, Managing Director of Inuka Microfinance Institution, said, “We are projecting longer relationships with these farmers and developing other products for them.”

The four selected commodities—sorghum, cassava, dairy, and chicken—while climate-resilient, are generally bought and sold in unstructured markets exploited by middlemen. Cassava and sorghum are considered subsistence crops by local Kenyans, sold largely in informal markets. Kienyieji chicken is an indigenous variety that is mostly reared in backyards. While a structured market for dairy products exists, producers struggle to achieve sustainable practices and adequate productivity. FICCF’s capacity-building support up and down the four value chains has helped to establish scalable and sustainable formal commodity markets where previously there were none.

Sorgum is proving to be more climate-resilient than maize because it is naturally drought- and heat-tolerant. Photo: DFID StARCK+.

As a result of these more structured markets, the microfinance institutions are now seeking additional investments through which to scale up their lending potential, and DAI is working to attract agricultural and social investors and other forms of capital to expand the approach to additional countries and value chains.

Applying Climate-Smart Agriculture Principles

The FICCF hits three climate-smart agriculture principles—demonstrating productivity, adaptation, and mitigation benefits:

- Productivity: Dairy farmers who adopted zero-grazing systems and improved fodder production have increased their yield from 5 liters to 10-12 liters of milk per cow per day. Cassava and sorghum farmers who access improved seeds through aggregators and apply the guidance received from extension, demonstration, and climate advisories are also generating higher yields.

- Adaptation: Dairy farmers gained knowledge on fodder conservation techniques for dry season feeding and lactation planning to help stabilize production throughout the year, making them less vulnerable to seasonal climate variability.

- Mitigation: Compared with extensive grazing systems, the fodder mix promoted by the FICCF will reduce greenhouse gas emissions per liter of milk by increasing total milk production per cow. The FICCF’s aim has been to contribute to reducing herd size while increasing milk yield per herd. Other new practices made possible by FICCF include the adoption of energy efficiency (solar and treadle pumps), renewable energy (biogas), and energy audits for agribusinesses.

FICCF catalyzed a gradual switch to more resilient crops: from maize to more drought-resistant and early-maturing sorghum varieties and intercropping with legumes. It also tested a hybrid insurance with weather index and multi-peril cover for disease and pests with 150 farmers. In the 2017 season, 35 percent of farmers received a compensation payout.

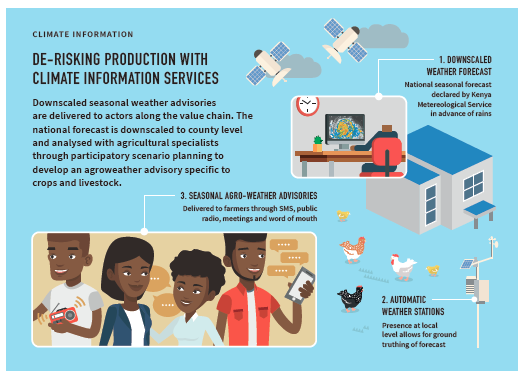

Click on graphic for expanded view.

Click on graphic for expanded view.

Filling in the Gap

In the past two years, the FICCF climate-smart agriculture intervention has reached more than 5,000 small farmers, contributing—in our estimation—to 12 of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals.

The broad range of expertise needed to apply this climate lens to agriculture—encompassing agronomy, veterinary services, energy audits, market linkages, institutional strengthening, and so forth—requires orchestrating a mix of private and public service providers, depending on the nature of the service.

Farmers are adopting more sustainable cooking habits, such as using biogas units. Photo: DFID STARCK+.

But this work should have long-term benefits. Smallholders who plant drought-resistant crops and practice sustainable farming will better secure rural food sources and build their resilience to climate shocks. Microfinanciers and agripreneurs are now better able to deal with the effects of increased climate variability in farming. And the farmers we have reached will in turn demand relevant climate information as they seek to adopt adaptive and resilient practices and utilize climate-smart technologies on their land.