Applying Market Systems Approaches to Financial Inclusion Projects

Sep 7, 2016

The market systems approach to economic development has gained prominence within development work that prioritizes inclusive economic growth. Donors such as the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), U.K. Department for International Development (DFID), and Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) have endorsed market systems development as a way to help large numbers of poor people achieve sustainable increases in income, opportunities, and resilience. In 2013, these donors formalized their agreement and pledged to work together on related research and learning.

Over the past decade, market systems approaches have been increasingly applied to financial inclusion work—connecting “unbanked” people to services such as savings, credit, and e-payments. This includes DFID’s Financial Sector Deepening (FSD) projects and trusts in Africa and ancillary components within larger economic growth projects. Drawing from DAI’s experience, this article offers lessons and practices that donors and practitioners may find useful as they apply market systems thinking to pro-poor financial inclusion work.

DAI implements market systems development projects for USAID, DFID, and the SDC. DAI is currently implementing more than 30 economic growth projects with a combined budget of more than $1 billion, each sharing the goal of increasing sustainable and inclusive economic growth. DAI launched FSD programs for DFID in Zambia and Mozambique in 2013 and 2014, respectively, and has worked in pro-poor financial expansion since 1980.

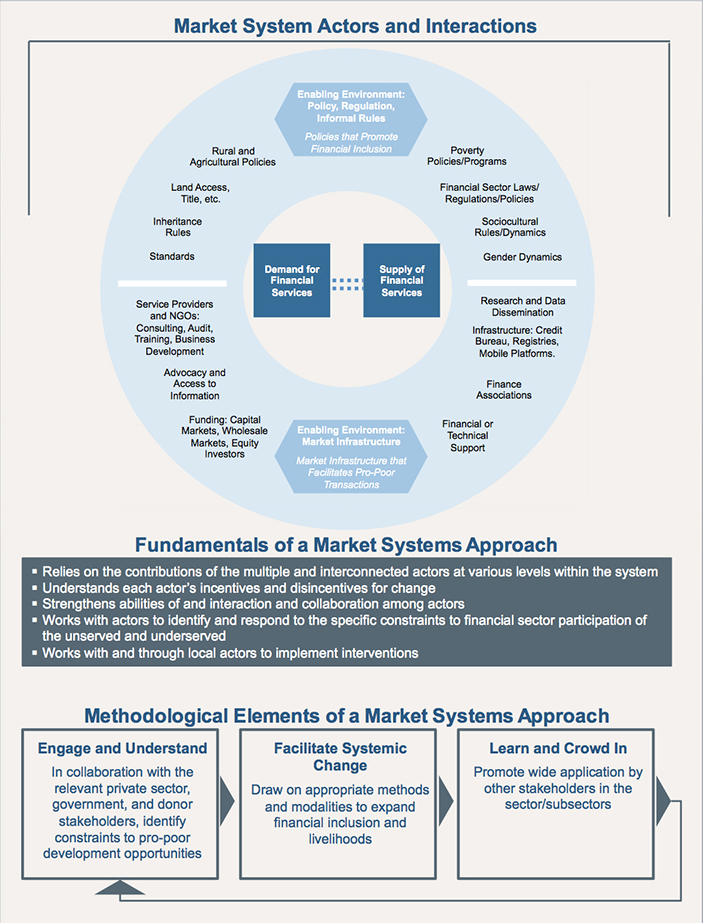

##Market Systems Development—An Overview

The market systems approach—also known as Making Markets Work for the Poor and by other names—relies on contributions from the totality of a system’s demand, supply, business-enabling, and government stakeholders. To include poor and marginalized households and enterprises in the formal financial sector, a market systems approach requires collaboration between government, financial sector infrastructure and supporting services, and key supply and demand players to identify and address constraints to financial inclusion, including doubts on the part of the unbanked or underserved and unwillingness on the part of financial service providers to serve these market segments.

##Applying Market Systems Approaches to Financial Inclusion

Applying a market systems approach can be more art than science because each financial inclusion project is unique. Certain market systems principles and tools are required, but equally important is for projects to perform activities that comply with exogenous factors—such as donor requirements, unique logical frameworks, market dynamics, and project tools and modalities. Projects rarely can apply a “pure” market systems approach but can uphold its principles, even if those principles are focused on a single component or target market.

In 2015, DAI developed and published “Market Systems Development: A Primer on Pro-Poor Programming,” an overview of market systems development and examples of interventions that have produced positive results. Presented below are additional key lessons from DAI’s implementation of financial inclusion projects that apply market systems principles:

1. To understand financial inclusion dynamics, you need to understand a variety of interconnected market systems.

As its name implies, a tenet of the market systems approach is to develop a deep and nuanced understanding across across macro-, meso-, and micro-levels within markets. While a focused market system (for example, trekking in Nepal) may benefit from a straightforward approach, the myriad markets that affect financial inclusion—including related products, services, institutions, and delivery mechanisms, as well as socioeconomic factors—are far more complex. Each influences customers’ needs, capabilities, protection, reporting and data, and access to technology.

Commercial banking, microfinance, insurance, digital financial services, and capital markets and equity investment all have supervisory structures, financial infrastructure, and demand and supply dynamics. Broad-based financial inclusion projects require sustained effort that keeps pace with these market dynamics and evolving stakeholders. Even project interventions that have a pre-focused design (such as mobile money) experience political economy dynamics that constantly evolve with new governments, ministers, and laws and regulations, along with rapidly evolving supply and demand.

Market Understanding. In FSD programs, teams spend four to six months mapping markets, analyzing the political economy, and identifying core constraints to pro-poor development. These assessments orient project design and monitoring and evaluation constructs; yet they are typically outdated within 12 months and regularly challenged when entering into project rollout or grant-making. In the absence of a formal re-analysis, direct stakeholder engagement and early project rollout or grant investments can provide teams with additional and updated information.

2. A positive political economy environment is crucial but complex.

Financial inclusion is not the purview of a single government unit. The Ministry of Finance and the Central Bank may share oversight of financial markets; telecom regulators are crucial to developing digital financial services, particularly in telecommunications-led environments; and education ministries are needed to promote financial literacy strategies. Other ministries oversee sectors where financial transactions happen—in agriculture, trade and industry, health, and elsewhere. The policy positions of each will have knock-on effects and require strategies to ensure cross-collaboration. Financial inclusion projects using market systems approaches must invest up front to build relationships across decision-makers and influencers. To keep abreast of political economy requires engaging key government champions, maintaining positive momentum, and leveraging local, regional, and international networks and forums such as the Alliance for Financial Inclusion and others.

National Financial Inclusion: A Shared Responsibility. Political economy analysis in Mozambique found that, contrary to conventional thinking, the Ministry of Planning and Development has a strong influence on the financial inclusion agenda. While the Central Bank is looked at as the operational arm for policy and regulation, FSD Mozambique is keeping attuned with that ministry and other government units to set a vision for financial inclusion.

3. The best financial inclusion goals are integrated with real economy issues and dynamics.

Financial inclusion should be promoted widely for what it is: a tool for unlocking opportunities in economic growth and stability in marginalized places. For example, by achieving financial inclusion, “banked” households and small businesses can access loans or payment mechanisms to acquire critical assets such as off-grid energy (such as solar), or higher-quality seeds or fertilizer that increase agricultural yields. More broadly, working in complement with a country’s economic development goals can maximize the potential for a market systems approach to mesh with other government and donor programming in ways that promote financial inclusion.

4. Strong demand-side analysis provides the backbone to product and marketing innovation.

While demand-side interrogation is critical to developing new products and marketing, it can also support advocacy, behavior-change communications, and financial literacy campaigns and facilitate partnering. Once policy and economic growth dynamics are understood, program teams can engage potential financial service end-users to ascertain their demands and identify providers that are best positioned to serve them. For example, it may be that community-based institutions are best positioned to serve certain rural communities rather than microfinance institutions or commercial banks. Facilitation teams can then proceed to encourage such partnerships, with demand-side analysis available to support the commercial negotiations.

5. It takes a village to achieve financial market systems change.

The commonalities around “financial inclusion” programming are growing. Global data sets such as the World Bank’s Findex, The Economist’s Global Microscope, and the Making Access Possible diagnostic and programmatic framework provide new platforms for articulating financial inclusion statistics, issues, and needs. However, at the same time, donor mandates for such programming can differ across sectors (agriculture, water, sanitation, competitiveness), market level (macro to micro), product or delivery mechanisms (microfinance, digital), and even target beneficiaries (women, vulnerable populations).

Projects within DFID’s FSD portfolio—including two implemented by DAI—can combine many mandates involving myriad market systems into single countrywide projects. Similarly, DFID is incubating financial inclusion activities inside of larger economic growth or business enabling environment programs, such as the Private Enterprise Programme Ethiopia and the DaNa Business Innovation Facility in Myanmar, also being implemented by DAI.

It is crucial for countries, donors, and implementers to “connect the dots” between parallel financial inclusion projects and their related market systems to share lessons and avoid duplication. When success does not come quickly, it is also important to fail fast and learn swiftly, with parallel project teams asking critical questions of themselves and each other.

6. Engage local knowledge and capacity at all times to stimulate change.

Sustainability is central to a strengthened enabling environment for financial inclusion, increased financial services and delivery channels, and scaled uptake. These positive changes require building the capacity of and linkages between local market actors and encouraging local ownership of interventions—efforts that will support lasting behavior-change within financial inclusion systems. Market systems approaches stimulate the conditions in which local market actors can collaborate, innovate, and adapt.

7. Investing project resources is a constant balancing act.

Ideally, project resources would be flexible enough to allow for a thoughtful sequencing of activities that address the core constraints to pro-poor financial inclusion. However, most donor-funded projects are driven by their respective logistical frameworks, budgets, and spending modalities (such as grants versus technical assistance). Pressure to show local results can lead to deal-making with the strongest local entities, that is, the ones that can absorb and manage technical assistance and funding. As a result, addressing macro- and meso-level constraints, which take more time to fix but can produce returns at scale, can take a back seat to local, quick wins. Projects can balance this potential conflict by working with stakeholders from these different levels to identify common, “synthesized” constraints, clearly articulate their importance, and then target these constraints.

8. Communications between team members can expedite the crowding-in process.

Strategic communication facilitates traction toward the development of an inclusive financial sector. Planned communication, such as through a call for proposals or innovation challenge, can help broadcast a project’s intentions and procure local information about markets, ideas, and participation. In the course of partnerships, teams should consider issuing external communications jointly and repetitively with local partners to help pull in others.

##The Importance of Being “Banked”

Informal mechanisms such as moneylenders and community based savings and credit groups are often the only available solutions in rural and peri-urban areas and they often provide a plausible option. However, their quality can be unpredictable and, in such cash economies, there is a heightened risk in transporting money as well as of exorbitant interest and fees charged. People in these households and businesses, which are are typically rural-based or economically marginalized, also do not have access to a variety of financial and payment services that may be relevant to their lives or businesses. In addition, low-income people are especially vulnerable to economic shocks such an expensive and debilitating illness or farm crops that are destroyed by weather or other phenomenon. By accessing more financial services, households and businesses can benefit from more predictable, stable, secure, and relatively low-cost services such as saving, borrowing, and paying on credit, including for necessities such as school expenses and farming supplies.

To be sustainable, financial inclusion projects require engaging the numerous markets that can stand between the suppliers of basic financial services and those who demand them. A market systems approach has proven to be a productive way to promote these engagements.