DEVELOPMENTS

Beyond the Washroom: Sustainable, Systemwide Approaches for Good Sanitation

Mar 22, 2022

After years of growing professional interest, economic analyses, and policy engagement on global sanitation issues, there is now a solid body of evidence on the value of good sanitation. But to achieve universal access to adequate and sustainable sanitation services, we must translate this momentum into action. The next frontier in sanitation will have to advance on many fronts—identifying champions who can articulate the rationale for good sanitation and influence other development partners and actors; recognizing the critical role of the private sector in extending public services; seizing opportunities to blend public finance with commercial investment for wider benefit; sustaining behavior change to drive demand for services; and using knowledge and training to scale promising approaches in new geographies and demographics.

This multiplicity of goals requires a reset in our thinking: sanitation is not just toilets, facility construction, and hygiene campaigns. Today’s sanitation interventions must integrate actions on governance, policy, regulation, and finance; empower institutions and communities—especially marginalized groups; and integrate tools and technologies that make good sanitation broadly accessible and, crucially, financially sustainable.

In more than a dozen countries, DAI is implementing sustainable sanitation approaches and transferring tools into local hands to scale results beyond the typical five-year lifecycle of project funding. The following examples offer some practical insights into how to achieve lasting access to sanitation and move toward universal coverage.

Digitizing Access in Urban Indonesia

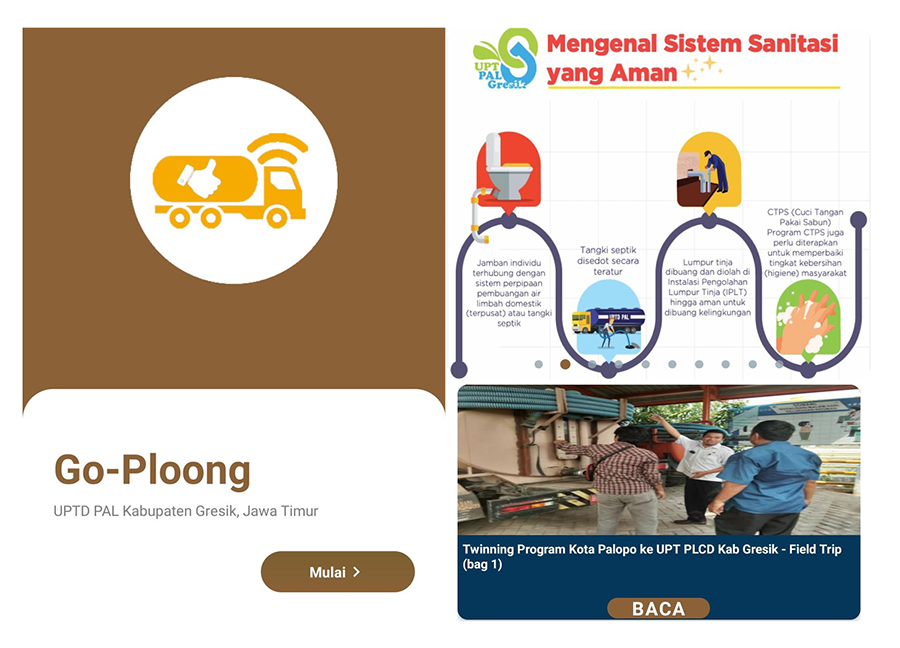

In Indonesia, where 90 percent of groundwater in bustling Jakarta is contaminated with E.Coli bacteria and 100,000 children die of waterborne diarrheal diseases each year, solutions extend far beyond hardware provision. DAI and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) implemented a multi-pronged approach through the Indonesia Urban Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Penyehatan Lingkungan untuk Semua (IUWASH PLUS) project, which improved urban sanitation by building local demand for sanitation services and then affording households with access to service providers through a mobile application called Go Ploong. Broadly, the project improved community access to septic systems and desludging services, boosted local governments’ ability to better manage sanitation systems and utilities, and facilitated joint investments by local governments, Central Government, and private sector firms to help maintain WASH projects and waste treatment services in the long run.

“Creating market demand for sanitation begins at the community level,” said IUWASH PLUS Deputy Chief of Party Alifah Lestari, which is why the project headed straight to communities and placed women at the center of the approach in 2019, promoting scheduled desludging services among groups of women from nearby households. Once enrolled, hundreds of pilot households received desludging services on a scheduled basis. At the same time, IUWASH PLUS worked with private sector sludge removal operators to improve their disposal practices and meet environmental and safety standards, while also linking them to the municipal wastewater agency to agree on regulations for safe disposal and treatment. The pilot database evolved into the Go Ploong app, which now links customers directly to a network of trained and qualified private service providers for safe and continuous desludging services.

In Indonesia, the key to a sustainable approach was creating a long-term market for sanitation products and services. “Together with the Government of Indonesia, USAID is [ensuring] that activities like desludging are self-sustaining beyond the project period—because they are creating a market for those services,” said Trigeany Linggoatmodjo, senior WASH program specialist with USAID in Indonesia.

IUWASH brought reliable water supply to more than 3 million people and safely managed sanitation services to more 960,000 city dwellers. Photo: USAID IUWASH.

Empowering WASH Innovations in Kenya

Kenya has seen steady improvements and reforms in the enabling environment for WASH, pioneered in part by the growing AfricaSan movement and Ngor commitments. Yet 40 percent of Kenyans still rely on unimproved water sources and 70 percent lack access to basic sanitation. The situation has grown more urgent during COVID-19 when good hand hygiene and the basic requirements of a sanitary environment are vital to reduce virus transmission.

To address these challenges, USAID’s Kenya Integrated Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (KIWASH) project set out to build demand for—and capacity to deliver—WASH services across nine target counties, thus providing incentives for WASH actors to fully meet needs for services. KIWASH not only supported local champions to carry forward good WASH practices, but it also leveraged public resources to scale up service delivery for basic and improved sanitation, while increasing access to finance and credit for WASH enterprises and utilities to successfully meet new demand. By reinforcing market-driven performance and supporting WASH officials at the county-level, the project improved the lives and health of around 1 million Kenyans.

KIWASH extended basic drinking water services to more than 874,388 people. Photo: USAID KIWASH.

In total, KIWASH trained more than 1,830 entrepreneurs—including water service providers and WASH enterprises—to promote and market improved sanitation options, including low-cost technologies such as SAFI latrines and SaTo pans. KIWASH helped incubate successful sanitation enterprises by supporting grassroots groups and local artisans with training to construct, install, and successfully market their products, thus improving local access to improved sanitation products, while also sustaining a market-driven revenue stream for the enterprises.

Retired pump attendant and community health volunteer, Timothy Kulavi, jumped at the opportunity to start his own sanitation business with support from KIWASH. Kulavi and around 250 other people were trained in the construction and marketing of low-cost sanitation technologies, such as SAFI latrines. He and the other trainees were then linked to around 100 grassroots community groups that help market their products and offer access to capital through pooled resources. To grow the businesses, community groups invested a total of nearly $14,000, with around $11,000 total in matching grants from KIWASH. As a result, this intervention helped more than 63,000 people access improved sanitation while creating job opportunities for many people.

Timothy Kulavi started his own sanitation business after receiving training and support from KIWASH. Here, he prepares part of a low-cost sanitation solution. Photo: KIWASH.

“The business not only improved hygienic practices in my community, but it created a new revenue stream for me,” said Kulavi. “The money I earn from my latrine construction venture has enabled me to pay school fees for my children at the university.”

In addition to entrepreneur training, KIWASH trained 231 WASH enterprises in improved service provision and supported nearly 300 WASH businesses with improved management practices or technologies. This helped more than 169,000 people gain access to basic and improved sanitation services. The project also worked on sectorwide governance through policy support that resulted in 26 new policies, laws, or investment agreements that promote better sanitation and water supply.

Securing the Sanitation Supply Chain in Haiti

In Haiti, a cycle of natural disasters and the high incidence of waterborne diseases have routinely shifted the country’s attention from long-term water and sanitation sector reform to immediate disaster response. Haiti’s National Directorate for Water and Sanitation (DINEPA) has focused on emergency response at the expense of longer-term planning for effective decentralization of WASH services. Public services remain limited, while unregulated private sector provision is often unaffordable or leads to environmental damage. Today, fewer Haitians have access to improved water sources than in 1990 and the country’s sanitation status is dire, with limited management of fecal sludge.

The USAID Water and Sanitation project is laying the foundation for sustainable, safe, and affordable access to basic and improved sanitation services that will reach 75,000 Haitians by supporting both the private and public sectors with improved service delivery and management. Safe sanitation can only occur if all three segments of the sanitation supply chain—storage, transport, and treatment/disposal—are safely managed. Thus, the project is strengthening the capacity of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to successfully market and deliver sanitation products and services. At the same time, the project works closely with DINEPA and regional water authorities, known as OREPAs, to help them effectively manage fecal sludge management (FSM) sites, both through facility rehabilitation and by developing realistic business plans for these sites that enable cost-recovery.

Demonstration of protective gear for manual pit emptiers in Haiti. Photo: Marie Maud Jean.

In Les Cayes, on Haiti’s southern coast, the project successfully addressed all three segments of the sanitation supply chain. First, it identified SMEs in the toilet and septic tank construction sector and provided them with registration support and technical and business management training. Successful SMEs were rewarded with grants to build toilets.

Then, the project supported an association of manual latrine pit emptiers to help them professionalize their work, register as companies, and get training on safe removal and transport of fecal sludge. The project also provided them with personal protective equipment and tools to ensure their safety, and the local OREPA arranged vehicles for the emptiers to rent to safely transport fecal sludge.

The Fonfred FSM site in Haiti reopened and operationalized with USAID’s assistance. Photo: Dan O’Neil.

Lastly, on the treatment side, the project provided technical assistance to reopen a previously closed FSM site in Fonfred (located within Les Cayes), in collaboration with the World Bank, which is financing the infrastructure rehabilitation. To ensure the site’s long-term sustainability, the project helped create a business plan that will enable it to reach its breakeven point within just five months.

Manual latrine emptiers in Les Cayes wear protective gear to ensure their safety. Photo: Marc Lee Steed.

The project’s model in Haiti emphasizes sustainability. Ensuring that utility and sanitation providers can recover their costs enables them to thrive in the long term, which in turn provides Haitians with the safe waste disposal needed to reduce waterborne disease. Best of all, the model is replicable across the country. According to the project’s Chief of Party Daniel O’Neil, “We’re trying to develop sustainable utilities. If we pull this off, Haiti will have clear models for how all the [utility service providers] should be functioning.”

Sustainable Solutions and Systemic Thinking

Financial sustainability and engagement across service providers, customers, and governments are the common threads in these examples. The path toward universal sanitation entails investing in approaches that empower communities and governments to implement and scale practices that make good business sense—whether by digitizing community access to desludging services in Indonesia, training county-level sanitation entrepreneurs in Kenya, or providing a roadmap for self-reliant FSM sites in Haiti.

Across the globe, smart sanitation must increasingly think beyond the construction of hardware—valuable as that is—and focus on the system-level changes necessary to make waste management an efficient and viable enterprise for the long term.

Kimberly Keeton is a strategic communications consultant. Email Kimberly here.