DEVELOPMENTS

Development During Quarantine: Lessons from Four USAID Projects

Oct 21, 2020

Mobility is fundamental to global development work. People, materials, and information must reach areas that can be geographically remote or underserved by communication infrastructures. The COVID-19 pandemic has changed an industry that can no longer rely on access to travel and face-to-face engagement. With COVID-19 a global reality for the foreseeable future, how can development projects continue to have strong impact when travel restrictions, social distancing, and remote work requirements are the new normal?

DAI’s projects around the world have spent recent months adapting to this new reality. In some instances, they have successfully pivoted in-person activities to the digital space. In others—particularly in areas that lack digital infrastructure—project leaders have creatively adapted to further their objectives in new ways.

Staff from four projects funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)—in the Philippines, Liberia, South Sudan, and Honduras—shared strategies for making a difference across physical distance.

Taking Environmental Enforcement Digital in the Philippines

The USAID Philippines Protect Wildlife Project works to conserve biodiversity while supporting sustainable livelihoods for local populations, particularly in Palawan, a biodiversity hotspot dubbed the “last ecological frontier” of the Philippines. In partnership with Palawan Council for Sustainable Development (PCSD), Protect Wildlife helps combat illegal wildlife trafficking and habitat destruction in the province. These are the kind of activities that, by definition, often require travel and must take place in-person—from venturing into protected areas for environmental crime enforcement training, to reaching remote communities, to conducting biodiversity research in the field.

A two-month quarantine for Palawan at the onset of the pandemic posed a challenge for the project’s efforts. Protect Wildlife found ways to keep two initiatives moving forward in the digital space.

The new Biodiversity Resources Access Information Network (BRAIN) System, developed with PCSD and launched on May 1, is a centralized database that supports online permitting, patrol management for officials, public reporting on environmental crime incidences, and case management. While the tool had been in the works since 2018, the project accelerated its launch in response to the quarantine.

In protected areas of Palawan, PCSD issues permits for activities such as wildlife collection and special use and local transport. In the past, these processes required in-person submission of physical paperwork. The new digital process lets PCSD personnel accept applications electronically, allowing the permitting process to continue safely despite COVID-19 restrictions. As of a few weeks ago, eight permits have been issued using the BRAIN System, mostly covering shipments of live reef fish for food trade.

Protect Wildlife also adjusted its approach to a public education campaign. The project’s Wild and Alive Campaign aims to reduce demand for illegally trafficked wildlife products through educational messaging posted at transportation and tourism hubs. After pilots in 2018 and 2019 in Manila, Protect Wildlife was just starting to expand the campaign to other provinces when the pandemic struck.

With restrictions on travel and transportation, the tourism industry came to a halt. Suddenly, the primary audience for Wild and Alive changed from tourists and travelers to people sheltering at home. The project was forced to reconsider its platform and content.

Protect Wildlife quickly reached out to partners—ranging from national parks to government agencies like the Department of Environment and Natural Resources—and turned Wild and Alive into a social media movement. The campaign now targets audiences in their homes with messages that encourage learning more about biodiversity, feeling responsible for protection of wildlife from illegal trade, making online pledges, and influencing personal networks. The team is also studying how to position biodiversity conservation and the illegal wildlife trade as public health concerns, making the topics even more relevant to the global situation.

When the Wild and Alive campaign could no longer target tourism hotspots, Protect Wildlife transitioned it online.

Recognizing Creative Solutions in Liberia

USAID Local Empowerment for Government Inclusion and Transparency (LEGIT) is in its fifth and final year supporting Liberia’s efforts to decentralize its political institutions and improve service delivery. Over four years, LEGIT has developed a range of governance tools and resources for county administrations and city corporation partners—and was planning to spend its final near focusing on sustaining impact after the close of the project.

Then, COVID-19 made its way to Liberia and the government declared a state of emergency and lockdown. The LEGIT team immediately asked: Could the project continue to focus on sustainability while also supporting the government’s COVID-19 response? And, importantly: Without the ability to conduct face-to-face meetings, what was even possible in rural, remote parts of the country where communications capacity and resources were limited?

To start, LEGIT identified which of its tools and resources could best support county and municipal pandemic response. Keeping long-term sustainability in mind, the team focused on helping partners implement standard operating procedures that aligned with COVID-19 efforts.

This work took place in remote counties of Liberia where internet access is undependable at best, electricity is sporadic, and many of the roads are inaccessible during the rainy season. Since most of LEGIT’s partners had mobile phones, or access to one, phone conversations replaced in-person visits as the project’s main form of engagement with partners. While unreliable phone service and connectivity expenses still makes communication difficult, the LEGIT team has found ways to stay in regular contact with partners.

LEGIT grantee Rural Engagement for Active Citizenship & Transparency (REACT-Liberia) distributes COVID-19 prevention materials in Konobo District, Grand Gedeh County. Photo: USAID Liberia LEGIT.

To generate solutions, LEGIT turned to its local staff. The project launched a “Work from Home Innovation Award” to recognize staff who found creative solutions to continue to support grantees, especially as they pivoted to assist in government COVID-19 awareness efforts.

LEGIT’s Participatory Engagement Coordinator Henry Stryker received the first award. Under a grant from LEGIT, Stryker had been working with civil society organization (CSO) partners to establish coalitions across eight administrative districts of rural Grand Gedeh County to raise awareness among locals about the Liberian government’s decentralization efforts. When COVID-19 emerged, these activities were no longer feasible—but Stryker saw an opportunity to put these local coalitions to a different use.

Stryker realized that important information about containing the spread of the pandemic was only reaching urban areas. He suggested to the head of Grand Gedeh County’s COVID-19 Incidence Management System that LEGIT’s CSO partners could assist with awareness outreach. The eight advocacy coalitions already had systems in place to disseminate information in remote areas; they could pivot from focusing on government decentralization to COVID-19 prevention.

“The work of these coalition members in reaching out to hard-to-reach communities and border villages near Cote D’Ivoire accounts for a huge success in containing the spread of COVID-19 in our country,” said Stryker, who managed to coordinate activities while himself working from home. “Bravo to the three LEGIT CSO grantees—the Center for Governance and Sustainable Development, Rural Engagement for Active Citizenship & Transparency, and the South Eastern Women Development Association—for their roles in supervising these efforts.”

Left: South Eastern Women Development Association (SEWODA), a LEGIT grantee, trained local coalitions to raise awareness on COVID-19 prevention. Right: LEGIT Participatory Engagement Coordinator Henry Stryker won an award for coordinating COVID-19 response from home, often working from the kitchen. Photo: USAID Liberia LEGIT.

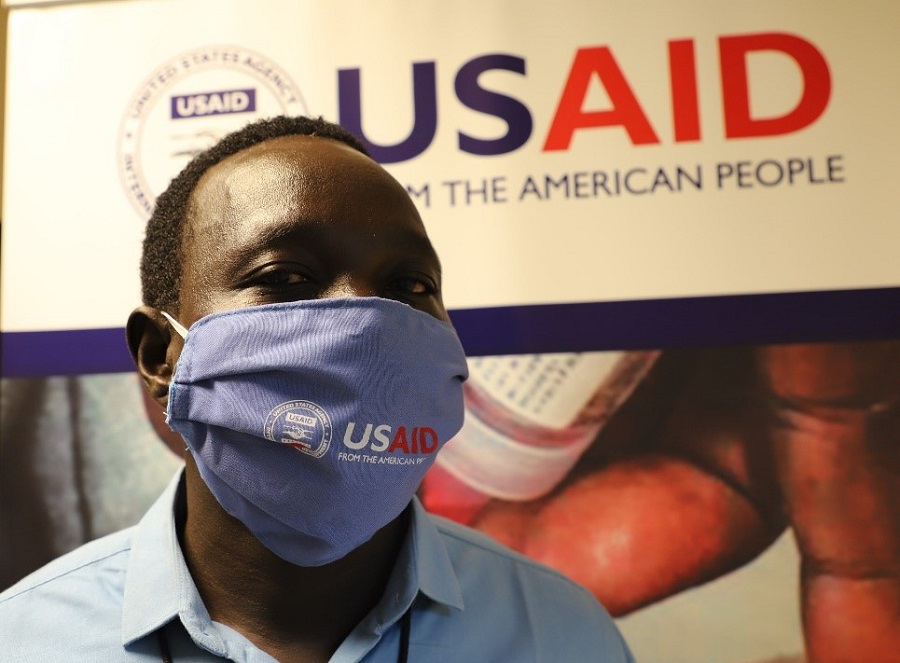

Ensuring Resilience in South Sudan

COVID-19 arrived in South Sudan just as the young East African nation was working to rebuild amidst political uncertainty and pockets of civil unrest. The country’s momentum was disrupted as the government instituted travel restrictions and curfews to control the spread of the disease. On top of this, the pandemic exposed infrastructural failures, brought on by decades of conflict and natural disasters, creating huge challenges for humanitarian and development efforts, not the least of which was communicating remotely.

The Policy LINK project—designed to support leadership and collaboration in agricultural systems and policy processes worldwide—had recently started work in South Sudan. Rather than developing policies outright, Policy LINK strengthens the capacity of local actors and institutions to lead the processes in their own countries and regions. The project provides backbone support to the Partnership for Recovery and Resilience (PfRR)—a multidonor initiative led by USAID—to reinforce existing community structures in South Sudan as they become more self-sufficient.

To continue this work amidst the infrastructure and coordination challenges brought on by COVID-19, Policy LINK partnered with another USAID project, SUCCESS. SUCCESS establishes community-based civic engagement centers (CECs) that provide internet, meeting space, training rooms, and computer access to remote corners of South Sudan. Run by local user committees, CECs proved an opportune resource for supporting connectivity and access to the international community.

Policy LINK is re-situating CECs as part of the project’s PfRR coordination. Through the centers and their User Committees, Policy LINK is supporting a series of dialogues, trainings, pause-and-reflect sessions, and other community engagement.

Photo: USAID South Sudan.

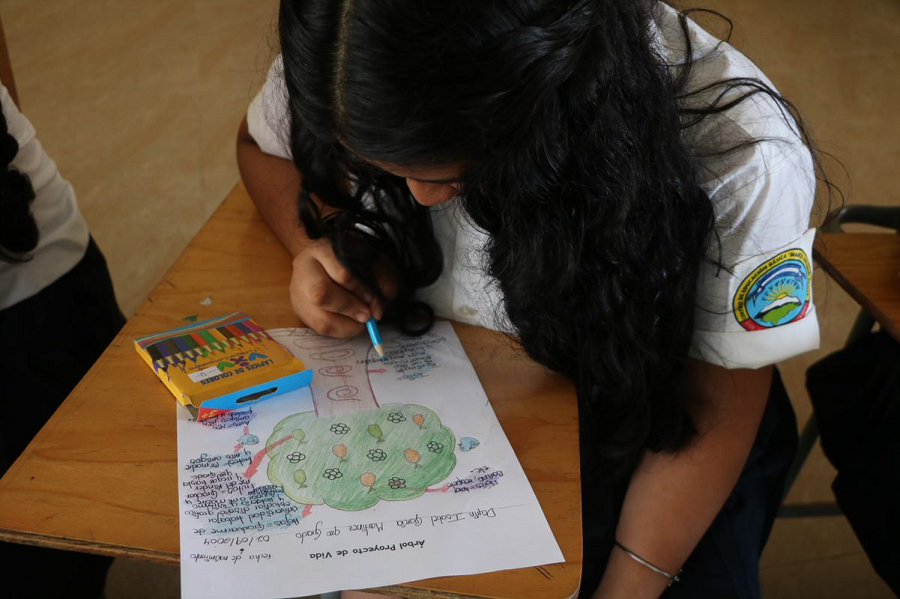

Supporting Educators and Students in Honduras

Since 2017, the USAID Asegurando la Educación (Securing Education) project has worked to reduce violence in schools, helping at-risk young people complete their educations and school leaders to build safer communities. Like education systems around the world, Honduras’s schools cancelled in-person instruction in early 2020 to control the spread of COVID-19. Already vulnerable students, without access to technology and basic necessities, became even more likely to drop out—and educators faced discouragement and mental health challenges as they struggled to help.

“One of my biggest worries is being able to maintain my staff’s motivation and [helping them] generate diverse opportunities so that the children have [access to] distance learning,” said Principal Otilia Padilla from Max Martinez School in Siguatepeque.

Asegurando had to adjust. For some initiatives, that simply meant moving online. The project adapted its existing Executive Leadership Program for Principals (PELE) to a virtual format, focusing on helping school leaders find solutions to distance education, motivate teachers and families, and keep students learning. The digital format allowed PELE to expand from serving 135 administrators to 1,000.

After training from PELE, Principal Padilla met with her school’s teachers to find strategies to help students without internet stay in schools. For example, in some cities, Asegurando-supported educators printed out hard copies of assignments and left them on students’ desks to retrieve at their convenience. Other schools moved internet routers to face the street to allow families to download and upload schoolwork.

To help students without internet access continue their schoolwork, some schools arranged for students to pick up hard copies of assignments from their classrooms. Photo: USAID Honduras Asegurando.

Padilla’s teaching staff remain committed to identifying measures to keep young people studying and helping them complete the school year. She said, “These processes of training help us to have a better understanding [of the obstacles] and to share [solutions] with parents to help reduce” migration.

Implementation in Uncertain Times

The COVID-19 pandemic forced the development community to quickly adapt to continue essential work around the world. As the crisis unfolded, DAI project teams and their USAID counterparts found creative strategies to keep activities going while ensuring staff safety.

In fact, DAI is no stranger to projects that require remote implementation and the flexibility to pivot based on changing conditions on the ground. Our Center for Secure and Stable States works to deliver impact in fragile contexts and has a global reputation for providing innovative assistance after crises and political transitions.

“I think that a significant reason for why we have been able to continue implementing and achieving our projects’ development objectives during these uncertain times is that DAI has a long history—and the approaches, tools, and adaptations that come from that long history—of remote management and remote implementation in conflict countries or in disaster zones,” said Tine Knott, Senior Vice President of DAI’s U.S. Government Business Unit.

Lessons from projects like Asegurando, PROTECT, LEGIT, and Policy LINK informed DAI’s early response to COVID-19. And these initial lessons in remote management—whether employing digital technology or leveraging community relationships—will continue to inform how our projects continue to adapt in a changing, post-COVID world.

Claire Miller is a Senior Communications Specialist at DAI. To learn more about how DAI projects are responding to the pandemic, visit our COVID-19 page.