DEVELOPMENTS

Financing Sustainable Land Use—Three Models From Brazil

May 16, 2022

Spurred on by decarbonization commitments, governments and the private sector are looking for new ways of reducing emissions to achieve Net Zero targets. This quest has renewed interest in the role of forests in avoiding emissions and sequestering carbon, as well as the part played by supply chains in driving deforestation. Reducing forest conversion is one of the most cost-effective options for reducing emissions, alongside solar and wind energy promotion, according to the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report (April 2022).

In the lead-up to COP26, the world’s largest financial institutions—representing $130 trillion in assets—signed up to the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), committing to reach Net Zero by 2050 and halve emissions by 2030. The Glasgow leaders’ declaration on forests and land use saw $12 billion allocated by donor governments and $7 billion by the private sector to fight deforestation and land degradation. Other initiatives include the recent European Union regulation to minimize EU-driven deforestation and forest degradation.

Such financial commitments and policies are a necessary first step. But it is equally necessary to understand the delivery mechanisms and financial models available to apply such funding and to grasp the incentives driving sustainable land use, in particular those at work in the private sector. Too often, that knowledge is in short supply. To address this shortfall in Brazil, DAI carried out a scoping study for the UK Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). The idea was to better understand the factors influencing deforestation in this critically important country—home to more than 12 percent of the world’s forest—and to explore innovative financial models which could lead to reduced emissions and greater sustainability.

Brazil is a relatively mature market—it has financial institutions and infrastructure to support small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) as well as international corporations and supply chains. We found a diverse mix of public sector interventions, public-private partnerships, and corporate initiatives, each with distinct innovations and benefits, making the country a great learning ground for other geographies and contexts. In this article, we briefly highlight three innovative financial models currently operating in Brazil’s Amazon states.

Brazilian rainforest land used for a variety of tropical crops. Photo: Adobe Stock.

Integrated Jurisdictional Approach

Produce, Conserve and Include (PCI), an initiative of Mato Grosso State, came about through a long process of engagement between stakeholders from public, private, and civil society sectors. PCI is one of the first jurisdictional initiatives in Brazil and indeed globally. (Further information on such approaches is published by the Carbon Disclosure Project.)

A jurisdictional approach brings together all relevant stakeholders from a given landscape, defined by political boundaries (usually local government). These stakeholders co-develop and align objectives aimed at promoting sustainable practices within the jurisdiction.

PCI takes an integrated approach that formalizes long-term commitments aimed at reducing deforestation through land use planning and policies, conserving native vegetation, and intensifying agricultural production in a socially inclusive manner.

While PCI is a Mato Grosso state initiative, it is actually led by an entity called the PCI Institute. An independent non-profit institution, the Institute was founded to coordinate the dialogue between donors and investors and raise the resources necessary to transition to sustainable low-carbon agriculture. The Institute’s development was financed by multiple international cooperation resources, including IDH and the REDD+ Early Movers Programme, GIZ, CDP, ISEAL, and the Tropical Forest Alliance.

Beyond advising on public policies and measures, the Institute enables multistakeholder coordination with state departments, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), private companies, and representatives from various economic sectors. It also provides technical assistance to smallholders. The PCI provides opportunities for international companies to collaborate with communities and producers in their sourcing regions while meeting their corporate sustainability goals. For the companies involved, the approach supports their supply chain traceability, monitoring, and verification efforts, and it improves their knowledge of local dynamics.

The PCI strategy implementation is financed by donor and private sector investments which are raised by the PCI Institute. The Mato Grosso State also finances 20 percent of the PCI strategy on activities such as land tenure regularisation and management of protected areas.

Most noticeably, Mato Grosso state was able to attract funds from Germany’s REDD+ Early Movers Programme. Jurisdictional approaches, typically led by subnational governments, appear to be well suited to attracting financial resources through international cooperation and could become an important conduit for climate finance reaching local actors. States, for example, are best placed to regulate the issuing and trade of carbon credits in their own jurisdictions. Doing so enables them to reduce distortions that may occur when voluntary initiatives are carried out outside of the state’s framework.

The PCI approach also offers a legitimate model to support Brazil’s compliance with its Nationally-Determined Contribution (NDC) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, as well as supporting local authorities and companies in meeting their voluntary climate action targets.

Jurisdictional systems development, however, requires hefty public budget resources and donor contributions to support the technical assistance aspect of the model. It also depends on strong local leadership and collective ownership. To replicate the approach in other geographies would also require adequate regulatory and institutional frameworks.

Green Business Accelerator for Producer Groups

Cooperatives and producer organizations are critical to keeping forests intact. Such organizations are often key land users and can be incentivized to pursue sustainable economic pathways employing regenerative farming models. However, these groups struggle to access finance earmarked for promoting sustainable agriculture because they are typically unable to meet the minimum business revenue requirements. Larger investment funds find it hard to adapt their structures to these “small ticket” agents.

The Conexsus Impact Fund focuses on delivering tailored financial services to community and small-scale enterprises. Conexsus invests in projects in their preliminary stages, opening up access to other credit lines as the project matures. Because the fund is based on blending finance from domestic public sources with private capital, Conexsus is able to offer credit at lower interest rates than the private market. Second, Conexsus only operates in environments where collaboration pre-exists through alliances that have been initiated by NGOs, SMEs, and larger companies. This prerequisite ensures a minimum level of aggregation and scale, as well as support.

The Conexsus Fund is the only blended finance fund dedicated specifically to greening existing Brazilian government credit lines. Conexus facilitates access to loans for cooperatives and SMEs that support sustainable production systems that keep forests standing. It does this by connecting local financial institutions offering government-backed loans with “credit enablers” who identify a pipeline of viable sustainable projects in remote areas. In exchange, these credit enablers receive a finder’s fee and repayment bonus for the loans executed.

The initiative is one of the few in Brazil that relies on a diverse mix of financing resources and agents, with varying finance terms based on business maturity stage, making it lower risk for all parties engaged. It also offers a strong social innovation component such as providing financial and business assistance to cooperatives and SMEs that would not otherwise be able to access rural credit lines at affordable rates. To date, the Fund has supported 7,500 families and helped preserve 175,000 hectares of Brazilian rainforest. Over time it is expected to achieve at least 900 million tCO2e in avoided emissions by preserving existing vegetation.

Supply Chain Carbon Insetting

Natura is a Brazilian-owned multinational that produces cosmetics. Known for its sustainable practices and use of natural ingredients, Natura sources its ingredients from RECA, a cooperative of more than 270 household farmers established 30 years ago.

RECA is located in Rondônia state, a region experiencing intense deforestation pressure from both livestock farmers and the logging industry. The cooperative has well-established agroforestry systems combining planting and conservation of native vegetation with agricultural crops and animal husbandry. Families manage some 1,000 hectares planted with more than 40 native fruit and timber species, producing pupunha heart, andiroba, cupuaçu (pulp, oils, and butters), coffee, and açaí—all organically certified.

Example of RECA’s Agroforestry Systems. Photo: www.projetoreca.com.br.

Since 2017, Natura has paid RECA annually for the environmental services its farmers provide by not depleting the legal forest reserves. These payments are made directly to families and into a cooperative fund. The practice—payment for environmental services within a company’s supply chain—is known as carbon inserting.

In addition to the ingredients supply contract, RECA and Natura have a 25-year agreement to reward avoided deforestation. The credits that arise from avoided deforestation are issued according to an agreed methodology that includes third-party verification and a baseline established yearly by reference to deforestation rates in the surrounding area.

The carbon credit methodology employed in RECA’s project was developed in partnership with Idesam, a nonprofit dedicated to the conservation and sustainable development of the Amazon. It was necessary to tailor the approach because certification methodologies and standards currently available (such as Verra’s Verified Carbon Standards and the World Bank’s FCPF) are expensive and not easily applied in micro and small-scale settings.

Providing credit for the additional carbon sequestration afforded by agroforestry systems is not yet an option due to the lack of appropriate methodologies and the high cost of carbon performance measurement. Should this change, producers would have access to additional revenue streams.

The RECA-Natura initiative demonstrates how carbon credits may be associated with an economic activity—in this case, RECA selling biodiversity products to a company. The income arising from the carbon credit sales is partly reinvested in the cooperative’s growth—a seed processing factory, for example—and partly distributed among its members.

In terms of conservation, the results are impressive. According to Idesam’s analysis, based on satellite imagery from the National Institute for Space Research, the average annual deforestation in the RECA lots is one fifth the average forest conversion rate observed on land in the same region.

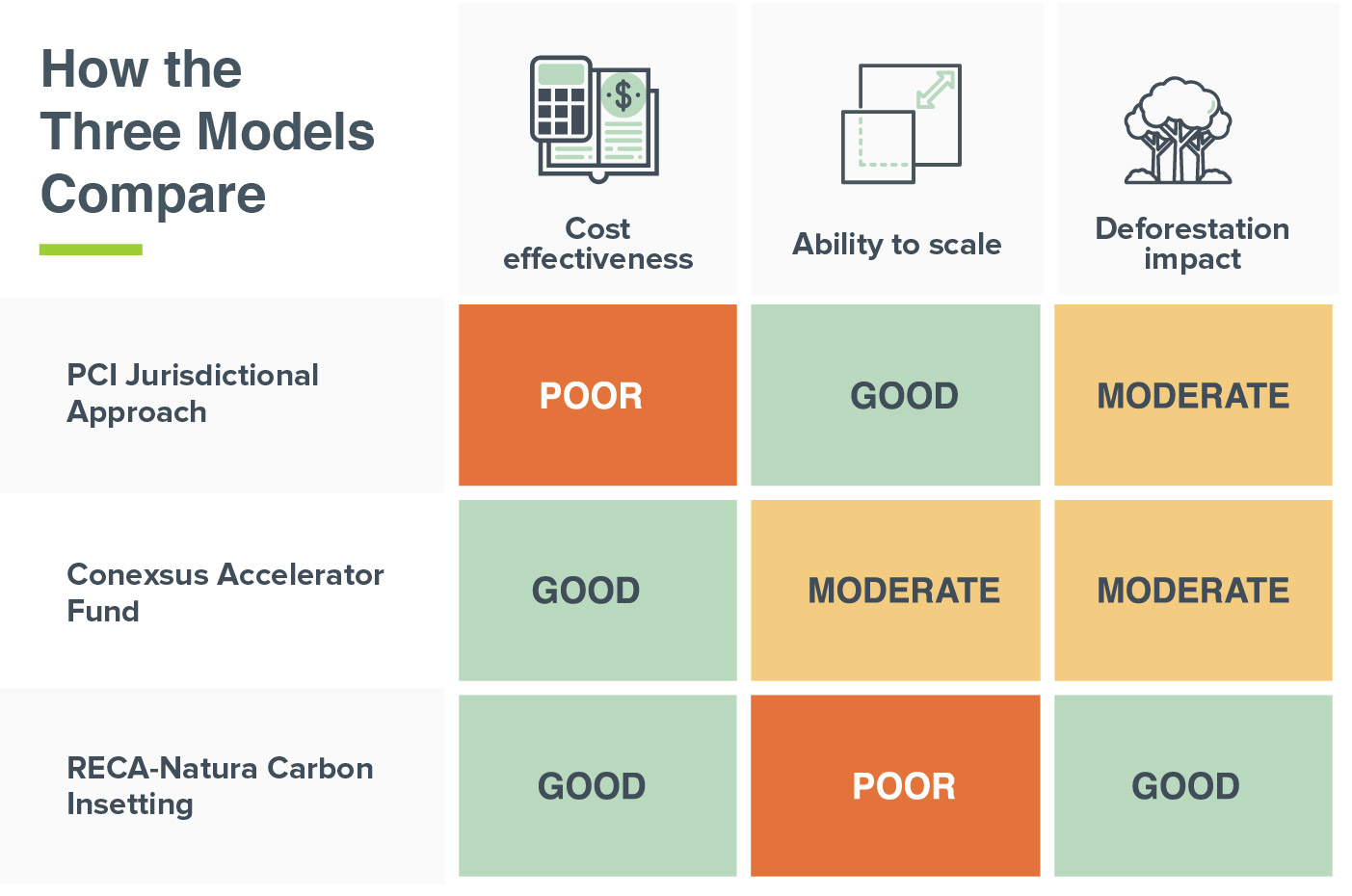

How the Three Models Compare

The PCI Jurisdictional Model works at a landsdcape level, achieving multiple positive outcomes and ensuring that sustainable, climate-friendly land-use activities work together with services that preserve the ecosystem and protect biodiversity. However, the model draws heavily on public resources.

The Conexsus Accelerator Fund deepens financial inclusion and offers farmers an accessible and cost-effective alternative to public systems and policies. One of its shortfalls is the size of its pipeline due to limited numbers of businesses that can present adequate risk levels and return-on-investment profiles, which makes it hard to deploy at scale.

The RECA-Natura Carbon Insetting Model has direct climate and nature benefits. Its scale is constrained by the order book and the amount of forest land managed by the community. It is, however, relatively easy to replicate so long as the demand for certified deforestation-free organic produce continues to grow. One limitation of the carbon insetting model is the need for farmers to hold formal land ownership documents.

Learning and Metrics Are Key

Each of these three models is unique, having evolved from a specific set of conditions and needs, but is potentially adaptable to other settings. However, if we are to connect such initiatives with the growing sources of funding for climate change-related projects, we need to better document and share their business cases and results, so that new, similar initiatives will receive appropriate consideration. Funding institutions—private and public—need practical tools to assess the impact of projects and activities focused on climate, biodiversity conservation, and livelihoods.

Practically speaking, that means funding more research into the impacts of different financial mechanisms on sustainable land use, particularly research that yields meaningful comparisons across those mechanisms (for example, how much carbon does a given mechanism sequester over a given period, and what social inclusion benefits does it yield?). And we need more insight into the reasons for the success or failure of these mechanisms, which will entail a deeper contextual understanding of their governance structures and enabling conditions.