DEVELOPING ALTERNATIVES

From Land Tenure Regularisation to a Sustainable Land Register

Apr 23, 2017

The evidence is clear: property rights are essential foundations for poverty alleviation and economic development. In Africa, it is less clear as to what may be the most effective way of establishing and especially maintaining those rights, with formal and customary tenure systems both offering degrees of security but radically different development possibilities.

Several African countries are undertaking large-scale, systematic land tenure regularisation (LTR) programmes—programmes to formalise and protect land rights—in rapidly developing economic and social contexts. Such programmes have been based on various definitions of rights including a long-term emphyteutic lease (in Rwanda); a lifetime “holding” right (Ethiopia); certificates granting rights of occupancy or customary rights of occupancy (Tanzania); or customary land rights (Namibia). All of these countries are currently grappling with the problem of how to sustainably maintain those rights once assigned.

The case of Kenya is an example where following the first registration programme, subsequent inheritance and sales were not registered because Kenyans did not understand the land registration system, lacked ready access to it, and faced inordinate costs in terms of time and money to use it. Informal transactions ended up causing more disputes than previously, in part because the traditional methods of dispute resolution were no longer usable since the land was now privately owned. Hence, the expected economic impacts—more land sales, greater access to credit, and consolidated holdings leading to more productive farmers—failed to materialise.

Put simply, registration by itself is not enough. Establishing the register is an important first step, but maintaining that register requires that people understand the need for recording changes in land occupancy, are motivated to participate in the system, and have an effective facility for doing so. In Africa, it has proved very difficult to build and maintain the technical infrastructure to support ongoing land and property transactions, in contrast to Eastern Europe where demand and awareness is high and the infrastructure has been developed in a relatively short time.

The answer, we believe, is a “fit for purpose” paradigm in the spirit of that laid out by Stig Enemark, Keith Bell, Christiaan Lemmen, and Robin McLaren. In this paper, we put forward such a model for a local, low-cost land register—the Technical Register under Social Tenure, or TRUST—that can be customised, deployed, and operated in a sustainable manner.

Regularising Formal or Customary Land Rights

Land matters in Africa have received a great deal of attention in the past 10 years. Population growth, demographic movements, and large-scale agricultural investment (especially since 2008) have placed land resources under pressure. Increasingly, land administration agencies are being pressed by the public, by investors, and by politicians, yet they have limited capacity, infrastructure, and financial resources to provide the secure land administration and management services these stakeholders demand. Recent initiatives—such as the Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security; the Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems; and African Union land policy—have highlighted the importance of land governance and spelled out the proper goals of land policy. But they do not set out practical measures that can be implemented at a reasonable cost and on a reasonable time scale. That said, positive developments are emerging:

Low-cost mass registration at a national scale is now a reality. The fit-for-purpose paradigm offers policy makers practical advice on reform based on simple solutions such as adopting general boundaries, using aerial images to identify boundaries, and agreeing acceptable accuracies for survey work. DAI pioneered such an approach in Rwanda where more than 10 million parcels were registered in five years at an average cost of less than US$7. This methodology is now being applied in Ethiopia on an even larger scale.

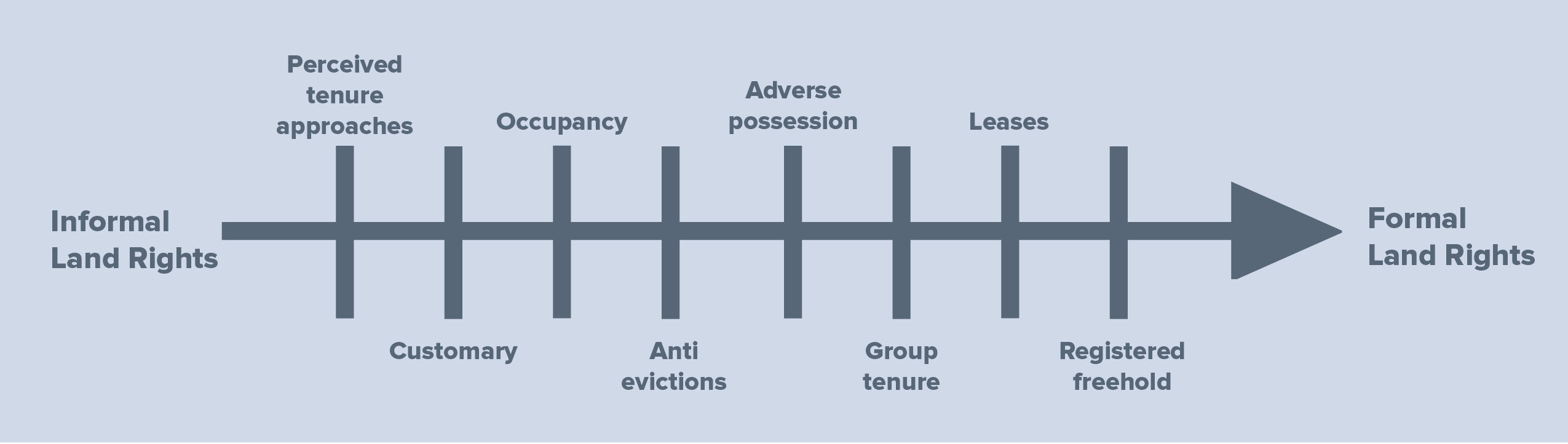

The continuum of land rights model bridges formal and informal land rights. Historically, we have distinguished strongly between customary and formal tenure systems. But the continuum of land rights model endorsed by UN Habitat (below) asserts that land rights can have a continuous spectrum, and it is possible to “register” or record any of these rights. In European land administration systems, we consider the formal registration as a kind of juridical cadastre, wherein rights, parcel extent, and position are legally established. Traditionally, we consider the recording of informal rights as something informal, and we regard the formal registration as superior. Hence we usually try to regularise informal land rights and convert them to some kind of formal right that can be formally registered (for example, in a lease). We could, though, look at this another way: why not record the informal right, especially if this right has strong social standing and is accepted as legitimate?

We can register both formal and informal rights, and they can have legal and/or social legitimacy. We can extend the continuum of land rights model by also considering the formal registration or informal recording of these rights. We simply record the informal or customary right, without converting it to a formal land right first. Increasing evidence suggests that customary land tenure systems and informal markets are able to support access to land and meet local land occupiers’ needs; indeed, this is a central tenet of Urban LandMark’s incremental tenure improvement approach, where local recording of land rights is regarded as a potential first step toward eventual formal recognition, while providing some level of recognition and evidence of occupation. This thinking suggests that we can often deliver legitimate land rights simply by recording the customary or informal rights—in line with the Social Tenure Domain Model—and without converting all rights to formal rights as part of the registration process.

![LAND Diagram 2 Land Rights - f2v1[3]](/uploads/LAND Diagram 2 Land Rights - f2v1[3].png)

Interestingly, a recent literature review by Geoffrey Payne and colleagues shows that a number of approaches and interventions have been successful in fostering legitimate tenure systems and achieving positive development outcomes. These approaches include freehold ownership through land titling; leasehold; land registration and land use certification; community land trusts; common or communal ownership; and private land rental. While we tend to place most emphasis on formal titling, Payne’s findings suggest that other tenure forms may also be effective.

Needed: Innovative Solutions to the Registry Challenge

In the 21st century, land administration systems will nearly always be developed using digital systems. Assuming they are well designed, then they are more secure, more efficient, more transparent, and more accessible. However, land administration initiatives worldwide are littered with failed large information technology (IT) projects.

Rumyana Tonchovska and Gavin Adlington have reviewed various approaches used in modernising the land registration systems of Europe and Central Asia, where the World Bank committed more than $1 billion between 1990 and 2012. Rather than “big bang” IT projects, the most effective approach turned out to be incremental, step-by-step developments accompanied by strong local involvement. In most countries, land administration services are typically the responsibility of government and resourced by the relevant government ministry. To establish the required information management system, a responsible body—often a ministry—conceives and implements a large IT project to integrate all land-related geo-information and associated data, with the intention of cascading that information down to local agencies. The problem is that these projects tend to be of immense size, duration, and complexity, and they are often trying to meet the needs of quite separate business units. The projects can become bogged down in procurement, design, or implementation, and the funding requirements for roll-out, support, and operation can be unsupportable.

Africa is no exception. In Africa, there are at present no automated land administration systems operating at a national scale and able to provide services at local, regional, and central levels. By contrast, many of the countries in the Europe and Central Asia region are now rated in the top 20 or so countries for ease of transfer of property rights, according to the World Bank’s Doing Business index.

Responding to this phenomenon, Robin McLaren in 2011 proposed a radical new approach to registering and then managing land rights, whereby citizens or citizen groups can be engaged in a new, collaborative model, directly declaring their rights through an open data initiative using mobile devices. This proposal, in turn, led to the establishment of the MapMyRights and Cadasta initiatives. The latter is currently building a cloud-based platform to host field data collected in this manner.

In addition, open source software—especially geospatial applications—is dramatically changing the price/performance relationship, and offers the prospect of geospatial solutions cascading to local districts without significant software licensing costs at that level. Open source solutions such as the Food and Agriculture Organization’s Solutions for Open Land Administration and Open Tenure (SOLA Open Tenure) have been trialed in Cambodia, Nigeria, and Uganda. Today, we see various registry solutions being tested:

- Traditional integrator/vendor solutions (such as the Integrated Land Management Information System now under construction in Tanzania)

- Open source generic solutions (such as SOLA Open Tenure)

- Global technology platforms, with crowdsourcing or intermediaries (such as Cadasta)

While each approach has its advantages and disadvantages, we should recognise that the requirements for an urban land administration system—able to meet the needs of Dar es Salaam, say, or Addis Ababa—are quite distinct from what is needed by a village or district in rural Tanzania, or northern Namibia. Given the relatively robust property market in the larger urban centres, especially with regard to the value and volume of transactions, it is likely that cities enjoy enough demand to stimulate and sustain a functioning land administration unit suitable for their needs.

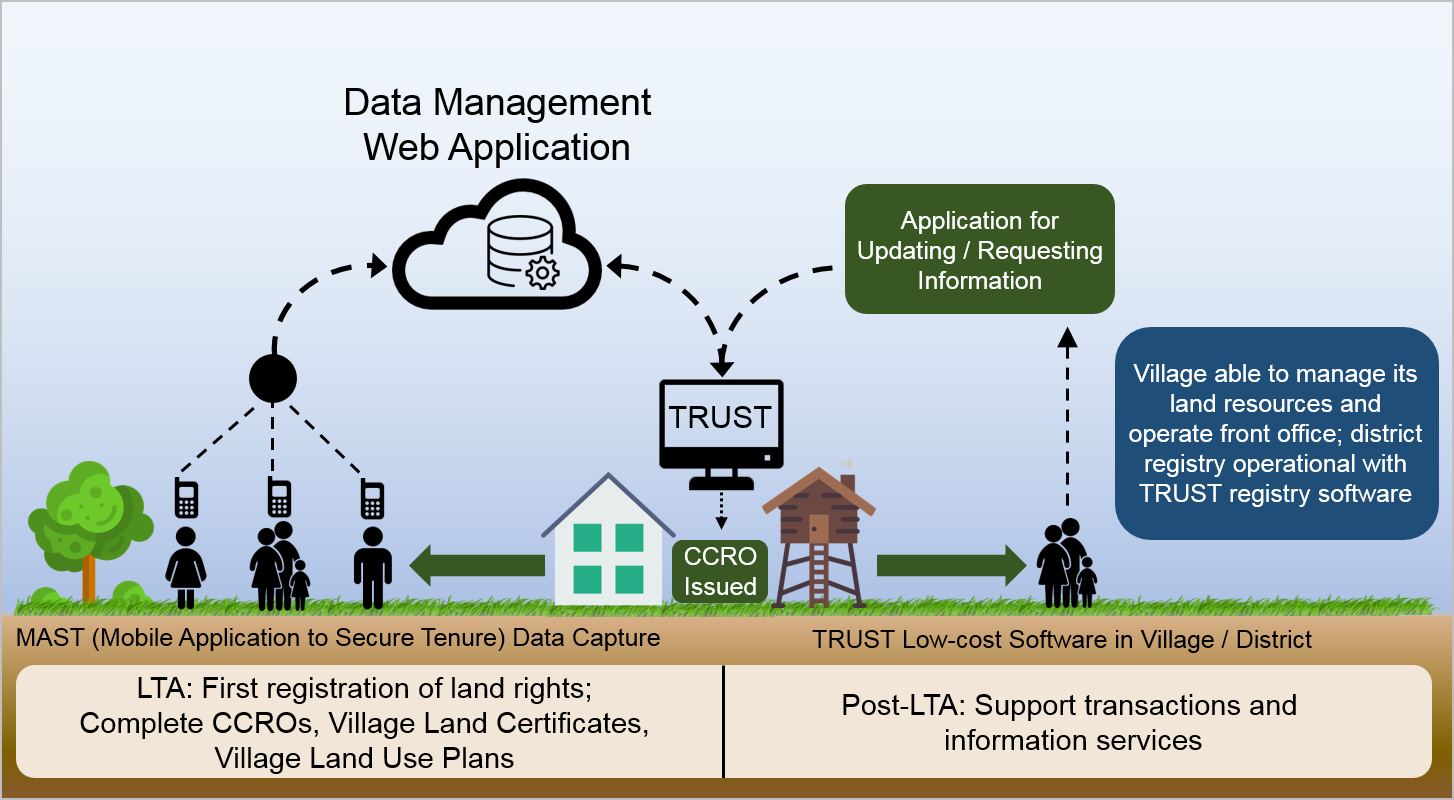

Outside of the urban centres, the demands are quite different. In Tanzania, for example, the system is heavily decentralised and the administration is at the local district and village level for all village lands (70 percent of the country, encompassing an estimated 13,000 villages). Yet there is little chance of providing automated land registry services at that level. In Tanzania, accordingly, DAI is developing further the Mobile Application to Support Tenure (MAST) tool, which allows the recording of geospatial and other information using mobile technology. We are using MAST on the U.S. Agency for International Development’s Feed the Future Tanzania Land Tenure Assistance project to register land rights in 41 villages in the Iringa and Mbeya districts. Notably, though, this application allows the initial registration of land rights but does not support their ongoing management or updating. That is where TRUST comes in.

TRUST—Toward a Sustainable System

Following the fit-for-purpose principle, DAI’s Technical Register under Social Tenure system—TRUST—seeks to provide a local land registry based on open source software linked to a mobile device. Unlike Cadasta, the records will be managed locally, ensuring the communities themselves have ownership of and responsibility for the land administration system. The TRUST system is replicated to a remote host at least once every 24 hours. Where a national system exists, TRUST will feed data to it.

DAI will deploy TRUST initially in Tanzania, where it will be linked to the MAST application, as illustrated below. TRUST will have a simple data model based on the Land Administration Domain Model (ISO 19152), and will accept data from MAST or other entry devices. The communities themselves (with DAI facilitators) will be responsible for data entry, and it will operate in accordance with the requirements of Tanzania’s Village Land Act.

We believe that the TRUST approach has several key advantages:

- Communities can readily use it (and MAST) themselves, enabling them to carry out basic land administration services.

- The technology is low-cost, easy to use, and replicable—and, when deployed, should significantly reduce unit costs for increased volumes of transactions over the longer term compared to conventional registry solutions. It runs as an app, and to the user appears just like any other app.

- It is backed up daily. Importantly, any registration carried out using MAST—no matter how small or local—is immediately compatible with TRUST, enabling ongoing data management wherever data is being registered.

Looking to the Long Term

Any sustainable solution for land administration must manage local needs as well as offer opportunities for economic development, including sound external investment in the community, where local people engage with outside investors to their mutual benefit. While there are now many resources to guide private investment around land, little has been written about how to put in place low-cost, sustainable solutions that support such transactions. In our trial of MAST/TRUST, we will focus on meeting that need.

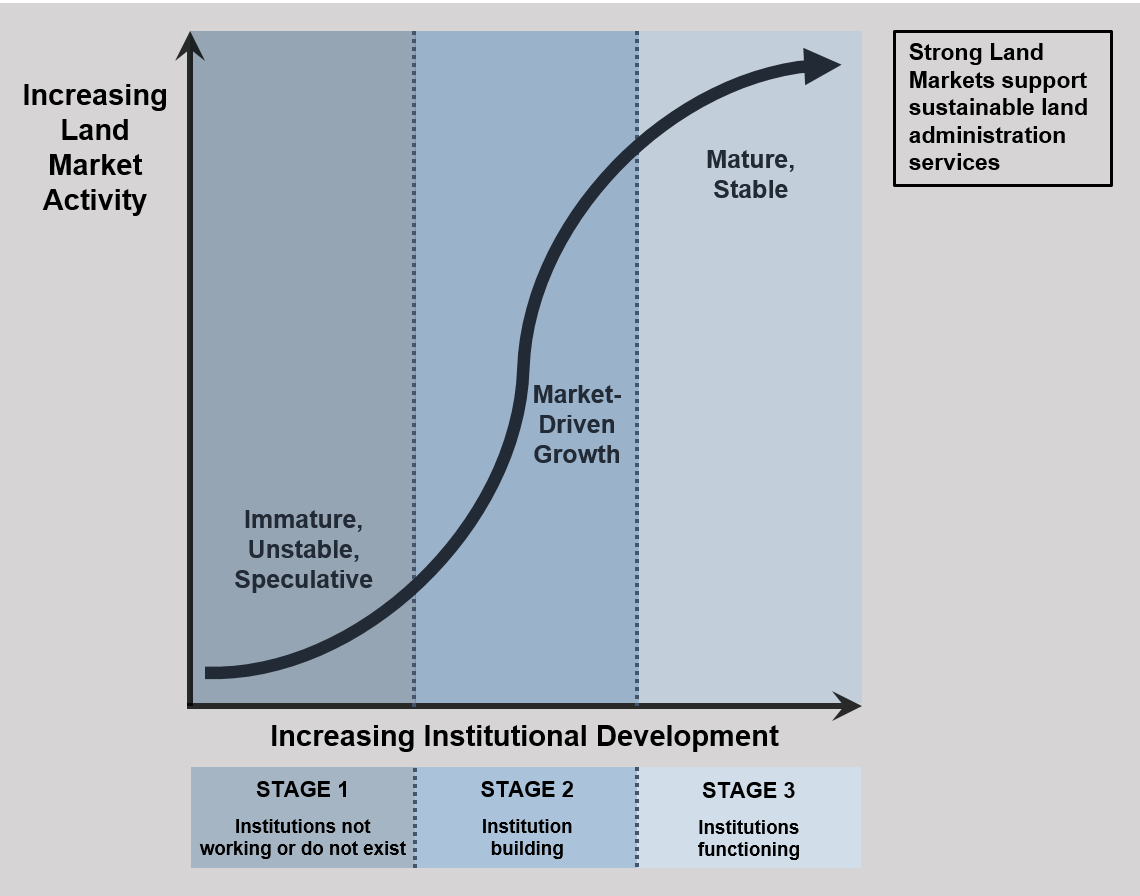

Longer-term sustainability entails both an effective mechanism for delivering land administration services and ongoing demand for them. TRUST can certainly provide the services, but will citizens demand them? Financing is also critical. In the European and Central Asian regions, many land administration agencies are now achieving significant cost recovery and in some cases even generating a surplus. This success is driven by land market activity. The figure below shows the land market model of development in Eastern Europe, where initial reforms and investment in land administration agencies established the infrastructure and capacity necessary for market activity.

(Source: Lessons Learnt from the Emerging Land Markets in Central and Eastern Europe, Peter Dale and Richard Baldwin)

In Eastern Europe, the European Union, the World Bank, and other donors led an intensive institution-building programme complemented by property privatisation, restitution, compensation, the creation of land registries and cadastral systems, and massive data creation programmes. As it became possible to transact, and financial instruments such as mortgages became available, the market took off and activity increased dramatically as demand grew. The result: within 15 years, most East European countries had built land administration systems supporting more mature, stable markets, with transaction levels similar to those of Western Europe.

In this model, the increase in capital availability and liquidity, access to credit, and the perceived security of tenure drove the market. However, this pattern is unlikely to be repeated in many African countries, so the demand will have to come from elsewhere. Just as we have seen a revolution in how LTR is carried out, so we need a revolution in how the registries can be established, operated, and financed. In Eastern Europe and Central Asia, demand rose as the economies aligned with Western European norms, and there was enough capital and liquidity generated by the economic transition to drive the property market (after initial reforms). In Africa, the demand needed to sustain land registration and administration services is more likely to come from investment-related activities (local and external), as well as normal community needs.

Conclusions

Our work toward a sustainable model of land tenure regularisation is underpinned by four observations:

- The goal of a land administration programme should be not just a first registration of rights, but a system that supports transactions and maintenance of the registry so that legal and physical persons can effect transfer or disposal in a secure and transparent manner.

- Low-cost local registries built on the TRUST model can complement registration programmes and ensure that the investment in registration is protected and its benefits realised in rural areas.

- Greater community participation and leadership in the registration process—suitably supported by tools and facilitators—is the wave of the future and should be embraced accordingly.

- Demand is a pre-requisite for sustainable land administration services.

In Africa, we see increasing pressure and demand from large-scale land investments. But this demand must be channelled in a way that delivers the benefits of investment yet protects the underlying interests of local individuals and their communities. Experience elsewhere (notably in Eastern Europe) shows that once we have achieved a critical mass of registration and deployed an effective registry maintenance system, then a land market emerges that stimulates investment and allows people to mobilise land and property assets in support of economic activity such as sales, leasing, real estate development, land improvement, and agricultural investment. It is from this land mobility that development benefits flow. First registration of rights, in and of itself, cannot support this mobility. But the TRUST application, premised on community participation and the availability of cheap and pervasive mobile technologies, promises to turn first registration into an ongoing register. We look forward to exploring its potential in Tanzania and beyond.