DEVELOPMENTS

How Can Developing Countries Identify and Allocate Resources to Pay for Health Services?

Oct 10, 2018

Governments in many low- and middle-income countries have committed to provide affordable and high-quality health services to their citizens. To make good on these promises, they need to identify more money for health expenditure and need to invest it more wisely. Our recent policy paper—Financial Management Mechanisms to Support Increased Government Spending on Health—provides some guidance on how they might do that.

To put the situation in perspective, government spending on health in the low-income countries we considered ranged from $2 to $41 per capita in 2015, while total spending on health per capita ranged from $17 to $107. The difference is often paid by donors and the low-income patients themselves.

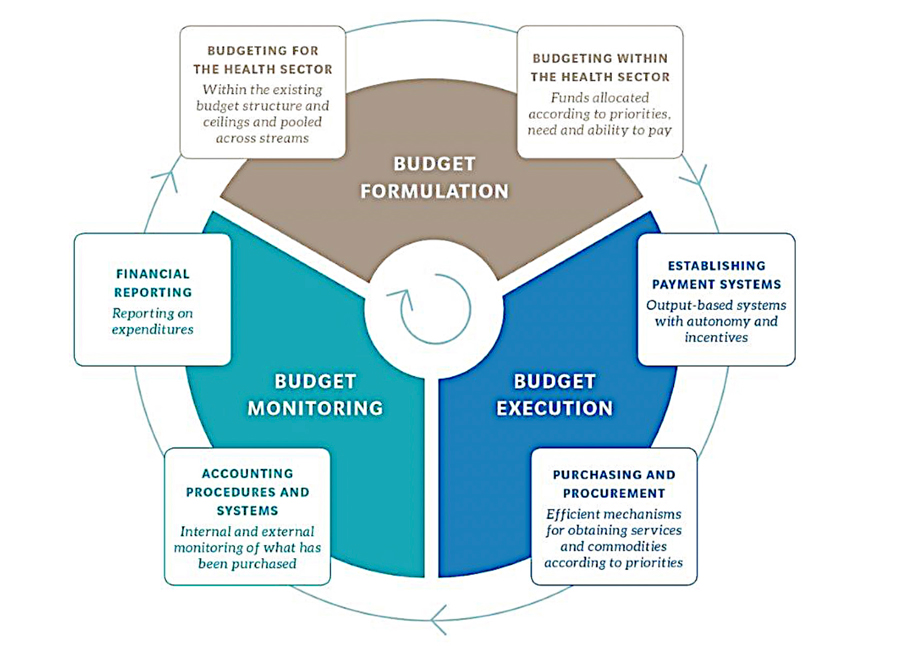

Prepared for the U.S. Agency for International Development’s Health Finance and Governance project, our policy paper explains how public financial management (PFM) mechanisms can be used to help countries increase domestic expenditure in their quest to achieve universal health coverage. Health system stakeholders—policy makers, executives, and senior managers—should learn how these mechanisms work so they can use them to inform and advocate for strategic health spending. These mechanisms are:

- Government financial management information systems (GFMIS) that manage revenue and expenditure;

- Revenue modeling and forecasting, which determine the overall budget envelope that constrains government spending;

- Medium-term planning and budgeting and program- and performance-based budgeting—key areas where health system stakeholders can engage in PFM processes and potentially influence budget allocations for public health; and

- Earmarking to ensure that sufficient government funds are allocated to public health, notwithstanding changes in political influences.

GFMIS—Armed With Information

GFMIS government accounting software packages manage all types of financial transactions. While cash-strapped countries need a functioning GFMIS to manage their overall finances, GFMIS is also required to implement other PFM mechanisms, including those that support health budgeting specifically. With a properly functioning GFMIS in place, countries can control payments, track expenditures, develop realistic budgets, and share government spending information to improve accountability and transparency.

But implementing GFMIS has proven challenging in many developing countries due to the limited capacity of institutions, long delays in implementation (for various reasons), and poor data quality. Governments may need to replace or upgrade their GFMIS, provide staff with better training on how to use the systems, and improve data collection and quality.

To put it in checklist form, governments should aim for their GFMIS to: 1) centralize all government financial transactions; 2) be used exclusively by all line ministries, including ministries of health, to process transactions; 3) capture all health expenditure data across the country; 4) prepare timely and complete government financial reporting; 5) fully implement Treasury Single Account—one virtual spending account within the GFMIS for managing government expenditures and payments, and; 6) improve cash management, which can increase fiscal space—or the flexibility a government enjoys in its spending choices—to allow for more money to be spent on health.

Health systems training. Photo: USAID Haiti Strategic Health Information Systems Program.

Forecasting and Budgeting

Revenue forecasting is critical. Ministries of finance forecast revenues to guide revenue authorities on collection targets and support the budgeting process. But in many countries, revenue forecasting remains unsophisticated. Inaccurate revenue forecasts create uncertainty in budgeting, regardless of whether the forecasts are too high or low—low forecasts mean more funds are available than anticipated, while high forecasts can cause funds to be reshuffled, potentially away from health.

Budgeting mechanisms represent the key area where health system stakeholders can influence the level of public health expenditure. While most countries have introduced some form of medium-term planning and budgeting, these countries—and donors providing technical assistance—should assess how well these PFM mechanisms perform because they provide a foundation for more advanced budgeting techniques.

Program-based budgeting, which itemizes program costs within the health budget, and performance-based budgeting, which sets measurable indicators to those programs, present direct ways for health ministries and agencies to advocate for increased spending. This budgeting enables ministries to design programs to achieve specific public health goals and the budgets needed to meet them. It helps justify budgets based on increased specificity, and its implementation should increase transparency by enabling government to show the link between taxpayer funds and public health outcomes. For health system stakeholders, the ability to tie results to spending year-over-year is crucial to objectively making the case for increased spending on public health.

Some countries are moving toward performance budgeting, but most do not have the ingredients in place to satisfy key preconditions and effectively implement the reform. For example, while the government of Nepal has moved toward performance-based budgeting and sets concrete annual goals, it lacks effective expenditure controls and suffers from rudimentary and inconsistent budgeting processes.

While many ingredients for performance-based budgeting exist in low- and middle-income countries, they rarely have been implemented robustly or at scale. These countries need to improve human and institutional capacity for performance-based budgeting, develop better monitoring and evaluation capabilities, and enhance the quality of the data that feeds the process. To support their goals of increasing health expenditures, health ministries should be early adopters of performance-based budgeting and work with finance ministries to implement (and benefit from) budget reforms.

Community health workers graduate in Nigeria. Photo: U.K. Department for International Development Women 4 Health.

Don’t Turn Your Nose Up at Earmarks

Earmarks have won a bad reputation for their rigidity and distortive effects on budgeting. However, since government budgeting processes are often susceptible to political pressure, they may be a justifiable means to protect government health funds and demonstrate the government’s commitment to health. Health funding, in particular, requires significant and stable revenue collections, which will affect the choice of the revenue source for the earmark—payroll and consumption taxes, for example, may be appropriate. Policy goals may also come into play, such as using taxes on activities deemed harmful to public health, including alcohol and tobacco sales.

For example, countries such as Egypt, El Salvador, the Philippines, and Tanzania use payroll taxes to fund public health programs, including different forms of national health insurance programs, while Ghana and Chile provide examples of earmarking value-added tax for public health.

In summary, PFM mechanisms and PFM reforms can help national governments maximize the benefits of health spending, justify health budget allocations, and assure citizens and taxpayers that their resources will be well used. In Financial Management Mechanisms to Support Increased Government Spending on Health, we hope to guide governments and donors on how best to use these mechanisms and achieve their health objectives, including for universal health care, and ultimately assist developing countries to be more self-reliant.