DEVELOPMENTS

Making a Difference in Orangutan Conservation: The Importance of Building Trust Among Stakeholders and Using New Communication Tools

Aug 15, 2022

In the more than 10 years since the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) funded the Orangutan Conservation Service Program (OCSP), led by DAI in Indonesia from 2007 to 2010, the world has changed in many significant ways, some expected, some not, some hoped for, some not. Some of the initiatives started under the project contributed to positive developments that continue to this day, while other changes could not have been predicted but are, nonetheless, opportunities to be capitalized on if Indonesia’s iconic “people of the forest” are to thrive.

The orangutan population is still under threat, its habitat reduced and further fragmented by encroaching timber concessions, plantations, mines, roads, and other human activities. But there is some cause for optimism. The decline in the number of orangutans in Indonesia has started to slow, now standing at about 104,700 (Bornean), 13,846 (Sumatran), 800 (Tapanuli) animals, according to the World Wildlife Fund in 2021. The struggle to boost those numbers continues, and former OCSP team members have taken forward the holistic and strategic approach of the project, responding to new challenges and opportunities in the past decade. In interviews with former OCSP team members, they compare then and now and consider how the picture has changed for the orangutan, what has been sustained following the project’s contributions, and what is needed for further improvement.

Then: 15 Years Ago

There is a sense that adversarial relationships between national and international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and private sector companies got in the way of advances in orangutan conservation. Negative assumptions about what other players were doing or planning meant that organizations were hobbled and lacked a complete picture of what could be done. Private companies developing plantations and other businesses in and near forests were not aware of how to “do no harm” and tended to block conservation activity, while NGOs, leery of the profit motive, did not want to engage with the firms or the government officials who were perceived to be handing out concessions that would further harm the orangutan and the forest. Worse, the orangutan was still hunted in many locations.

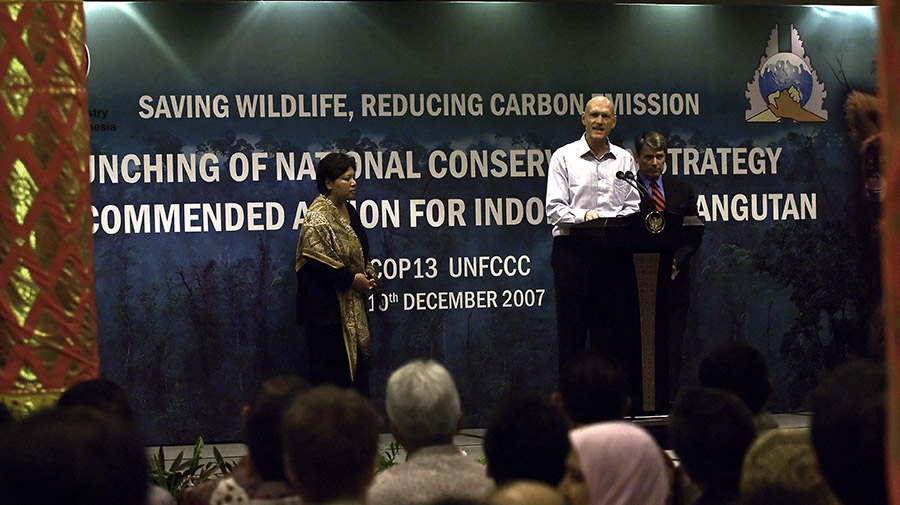

Early days of strategizing how to assist Indonesia in conserving the orangutan population. Photo: USAID OCSP.

At the same time, organizations working on orangutan conservation tended to focus exclusively on rescue and rehabilitation, and while their narrow focus undoubtedly made a difference to the orangutans they saved, they tended to miss the wider context and what was driving the underlying issues.

According to former OCSP Chief of Party Paul Hartman, now a Senior Environmental Specialist at the Climate Investment Funds, stakeholders recognized that “something needed to change, as the work of the various NGOs, while maybe successful at individual sites, was not preventing orangutan habitat loss writ large and USAID recognized that a more holistic approach was required to sustain viable populations across the country,” and they needed to focus on sustaining viable populations. “With more than 70 percent of orangutans living outside the national parks and in productive landscapes, we had to find ways to collaborate with a variety of nontraditional partners in order to find common ground,” he said.

According to former OCSP Chief of Party Paul Hartman, now a Senior Environmental Specialist at the Climate Investment Funds, stakeholders recognized that “something needed to change, as the work of the various NGOs, while maybe successful at individual sites, was not preventing orangutan habitat loss writ large and USAID recognized that a more holistic approach was required to sustain viable populations across the country,” and they needed to focus on sustaining viable populations. “With more than 70 percent of orangutans living outside the national parks and in productive landscapes, we had to find ways to collaborate with a variety of nontraditional partners in order to find common ground,” he said.

Hard as it is to imagine now, little more than a decade ago, projects such as OCSP got the word out about the issues and their work primarily through traditional media: radio, TV, and print were the most common means—far more difficult to exploit than today’s social media environment, where anyone can mobilize people around issues and share up-to-date information.

Photo: USAID OCSP.

What Was Planned—And Achieved

According to Hartman, who led the OCSP’s contribution to the 10-year National Orangutan Strategy (2007–2017) and helped establish the Indonesian Orangutan Forum, FORINA, “The orangutan conservation strategy along with increased government forest policy and regulation then created a better enabling environment for conservation. We are now seeing some positive results for Indonesia’s forests following the moratorium on new forest concessions, and actors across the palm oil supply chain pushing for sustainability.”

Other former OCSP teammates continue to lead in orangutan conservation today. “We made a strong base for orangutan conservation through FORINA,” reflected Jamartin Sihite, OCSP’s Deputy Chief of Party. Sihite is now CEO of the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation, where he builds on the policies and plans that he, Hartman, the OCSP team, and the Indonesian government started more than 10 years ago. “The national strategy became a mirror for the government and all organizations involved in orangutan conservation to look at to evaluate themselves and measure their achievement of targets, making their collaboration more effective and less sporadic,” Sihite said.

Former project Deputy Chief of Party Jamartin Sihite is now CEO of the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation.

Professor Erik Meijaard, an OCSP science advisor and now Managing Director of Borneo Futures, notes that OCSP data has contributed substantially to global conservation knowledge, including 20 high-level scientific publications. “The data was gathered from surveys where we collaborated with 20 local NGOs that interviewed 7,000 people across 700 villages, about orangutans and killings, environmental services, and deforestation at different scales.”

“We developed best management practices to support conservation management planning for orangutans within the plantations and to help companies recognize that they must be part of the conservation solution,” said Hartman. According to Dr. Sri Suci Utami, biologist and orangutan specialist, then with OCSP and now a lecturer and FORINA member, “More and more companies are using the best management practices and FORINA has provided training for company partners since 2007, using guidelines we developed for them to use and adapt for their unique situations.”

Some OCSP staff went on to bridge the gap between conservation and private sector agriculture initiatives. Orangutan conservation scientist Nardiyono used to survey orangutans in national parks and publish his work to the scientific community. He is now Head of Conservation at PT Austindo Nusantara Jaya Agri—a foreign investment firm engaged in the palm oil business—where he advises on how to conduct business without putting orangutans at risk. “Some of our conservation programs were adopted from my experience at OCSP…[including] how to engage the community, NGOs, and the local government,” Nardiyono said, observing that senior management commitment was key to shifting attitudes to orangutan conservation in his company.

What Was Not Expected, But is Having Impact

Changes in the wider world may also present opportunities for orangutan conservation. The recent increase in connectivity and ability to share and store data, and Indonesia’s massive adoption of smartphones and social media, all point to more ways to raise awareness about the need to protect orangutans and their forest habitats and at the same time to participate in tracking and monitoring them. “It is now easier to engage with multiple actors and use online platforms,” said Hartman, who thinks this kind of engagement on a global scale could open opportunities for financing conservation.

Given that most communication fora set up under development projects tend to fade as the initial energy and resources drain, it is significant that FORINA is still thriving. It now has an expanded scope, with its Jakarta-based national membership focusing on where change happens: in the regions. Regional orangutan fora in Kalimantan and Sumatera continue to monitor orangutan populations and drive conservation efforts, all the stronger for including “all kinds of stakeholders, not only scientists and NGOs, but also private sector companies, the government, and people who are interested,” said Dr. Sri Suci Utami, who recently completed a series of field monitoring visits to orangutan habitats under the auspices of FORINA in Aceh.

We Have a Chance

A national approach is important to set the framework for change and support it. However, the real work happens in the areas where orangutans, communities, and businesses are based. FORINA’s national forum sets out to support the regional efforts rather than lead them, visiting research stations in all the parks. According to Utami, FORINA is joining forces with other conservation partners in Sumatra and Kalimantan, with the support of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry’s Director General of Nature Conservation and Ecosystems, to find ways to collaborate on the conservation of Indonesia’s other endangered species including the tiger, the rhinoceros, and the elephant.

Sihite releasing a rehabilitated orangutan.

Meijaard is thinking about innovative ways to conserve the orangutan, having analyzed how much has already been spent to try to save the orangutan through various means. “We are now experimenting with blockchain payments where the orangutan actually holds a digital wallet from which he can pay the villagers for protective services,” he said. “This allows a direct financial link between someone on the couch in London and the orangutan deep in the heart of Borneo, cutting out all the overheads.”

Overall, 10 years on, there is a sense of cautious optimism among these former colleagues. They acknowledge that plantations and other businesses work in the forests, but that these companies can contribute to orangutan conservation. They agree that working with communities toward more sustainable livelihoods will make a difference, as will working with the Indonesian government nationally and in the provinces where the orangutans live. Connecting to people at their laptops in cafes as well as the communities who live in and near orangutan habitats will help. It might be tough at times, but in the words of Sihite: “We are struggling but working.”

Sheila Town is a consultant based in Indonesia.