DEVELOPMENTS

Meeting Kenya’s Water Needs by Positioning Utilities for Success

Aug 29, 2022

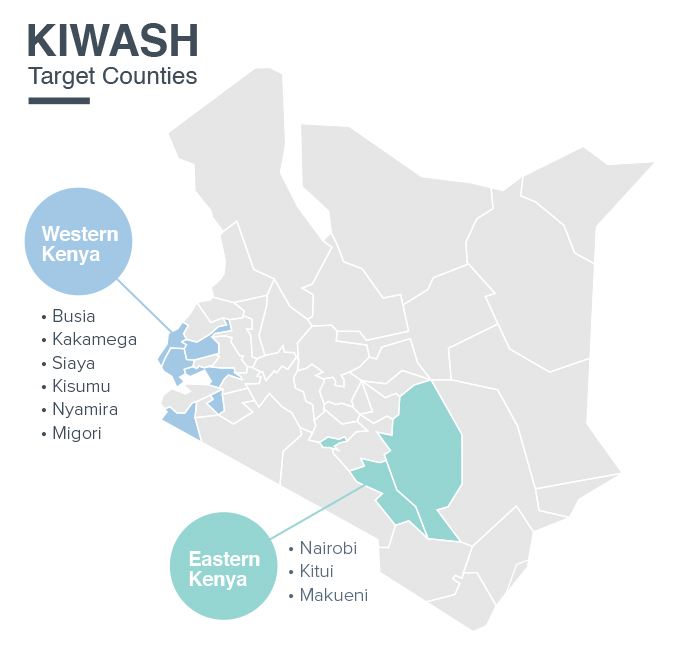

Since the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) launched a six-year water project across nine Kenyan counties, the country’s population has surpassed 50 million. That population is projected to double by 2050. To tackle the rapidly growing population’s needs, the water project, led by DAI, implemented activities that combined nutrition programming with improved access to water, sanitation, and hygiene—particularly in rural areas where nearly half the population lacks sufficient access to water.

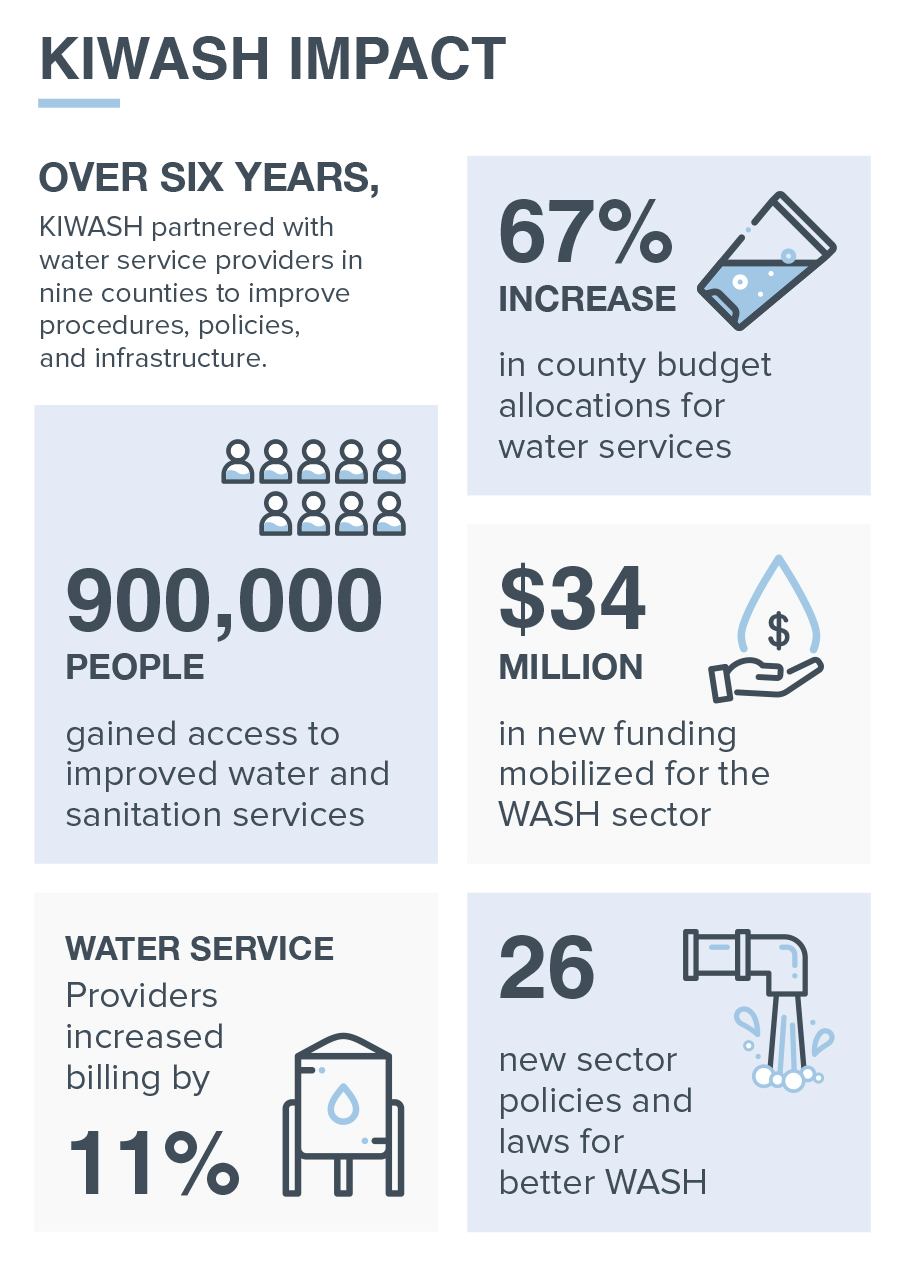

The results are now in. The Kenya Integrated Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (KIWASH) project enabled nearly 900,000 Kenyans to gain access to improved water security, sanitation, and hygiene services as well as irrigation and nutrition services.

Behind that impressive number was a collaborative approach that took its lead from Kenyan water service providers and the communities they serve.

Strengthening Water Service Providers and County Governments

Water service providers in the nine counties where KIWASH worked were massively underbilling their customers, in most cases by half. The payments they did manage to collect amounted to about 88 percent of the total owed. Prior to 2013, water services were handled at the federal level, so at the beginning of the KIWASH program most local water service providers simply had not been trained on their responsibilities and had inadequate policies in place around water service.

Our team worked closely with the formal water utilities, small WASH enterprises, local government officials, and communities to expand and improve WASH services. Governance was a core tenet of KIWASH because local governments play a key role in the decentralization of the Kenyan water and sanitation sector—and so the project sought to play a facilitative, and supportive, role in working with local actors to find solutions to challenges in the sector.

By 2021, these KIWASH partner service providers were able to increase their billing by an average of 11 percent and each of the nine counties—Busia, Kakamega, Kisumu, Kitui, Makueni, Migori, Nairobi, Nyamira, and Siaya—now has drafted water bills, water policies, and environmental health and sanitation bills.

County-Led, County-Driven

In forming county project teams—one per target county—and embedding select project staff within the nascent county water departments, KIWASH built trust between project staff and counterparts, allowing the project to gain a deeper understanding of the intricacies of each county. The KIWASH team was a supporting actor, encouraging counties to invest in service improvement and expansion while providing targeted support and training.

By working to increase tariff collection and improve operational and technical efficiencies—such as financial management, infrastructure management and repair, and reductions in non-revenue water—the providers, in turn, increased their ability to attract investment. KIWASH additionally supported lobbying efforts to achieve a 67 percent increase in county budget allocations for water services. “The professionalization of our services—courtesy of KIWASH—has seen us enjoy enormous support from partners,” said the Director of Water Services in Busia. “The county government has since increased budgetary allocation towards urban water to $200,000.”

To promote the sustainability of its activities, KIWASH paired all infrastructure upgrades with improvements in operations and maintenance support, creating a culture of ongoing maintenance and service provision, and ensuring infrastructure investments reinforce larger service delivery goals.

Investing in infrastructure was a major part of the project. Photo: USAID KIWASH.

Comprehensive Governance Support

KIWASH supported governance in two ways—working with county governments to improve the enabling environment through codified laws and policies to manage the water sector at the county level and directly assisting service providers to improve their own corporate governance.

Engaging early with county government officers, the KIWASH governance team identified areas of partnership in capacity development, planning and budgeting needs, and policy formation. It gauged the level of coordination between water service delivery actors so that it could determine what support was needed and better understand roles and responsibilities within the sector. And where possible it built on existing policy frameworks as the foundation for further development.

Predictably, conditions varied by county. In Makueni, project activities enjoyed the enthusiastic support of an engaged county governor. As KIWASH Chief of Party Japheth Mbuvi said: “In Makueni, we were lucky. We had a very involved, encouraging, supporting governor who took his time to want to know what we were doing and to be part and parcel of what we were doing. A lot of the things that we did in terms of trying to get the policies happening, trying to get the regulations happening, we really had his total support.”

In Kisumu, the project was not as lucky. A change in county government personnel halfway through the project interrupted the progress the team had been making. Without frameworks, policies, and procedures, and lacking formal roles and responsibilities beyond those established through individual staff understanding, the change in personnel required KIWASH to start from scratch. This setback underscored how much improvement was needed in county governance to ensure that systems and service delivery can remain intact through changes in government.

Organizational Challenges

It was clear early on that the water service providers were not operating to their potential, hindered by issues such as poor corporate governance, high levels of uncollected revenue, inadequate financial management, and low technical capacity. This organizational disfunction was interfering with the providers’ ability to attract external financing. In response, KIWASH developed performance improvement plans tailored to each provider.

In Makueni, a geographically large and rural county, water service providers were reaching just 35 percent of the population; water coverage was low due to insufficient supply and low production capacity and drinking water quality was often unacceptable. KIWASH developed tailored performance improvement plans with two water service providers—WOWASCO and KIMAWASCO—to address challenges in operational efficiencies, financing, and technical capacity. WOWASCO, for example, was in non-compliance with statutory and regulatory regulations and was unable to conduct tariff reviews due to low production capacities; KIMAWASCO was not collecting full revenue potential and was operating at a deficit even with staff salaries in arrears.

Addressing debt management with WOWASCO, KIWASH helped establish a debt collection committee that collected more than 35 percent of outstanding debt in six months. KIWASH additionally supported both service providers to address billing and collection inefficiencies, leading to improvements in services, revenue collection, and staff morale. WOWASCO improved the integration of billing and collection systems, developed water metering policies and practices, and used GIS to locate dormant water meters—replacing 176 non-functional meters; KIMAWASCO, similarly, replaced inferior meters and rehabilitated systems to prevent leakages.

All told, WOWASCO and KIMAWASCO increased revenue collection to 95 percent and 91 percent, respectively. With more revenue and less debt, KIMAWASCO improved its payment practices and bolstered morale. “When the company fails to remit staff deductions, [employees] assume that the management is ‘eating’ their money,” said KIMAWASCO’s Managing Director. “But as soon as you start paying their salaries on time, there is improved rapport, and they are motivated to work and deliver.”

WOWASCO worker on a pump system. Photo: USAID KIWASH.

Meanwhile, in Kisumu, the major service provider, KIWASCO, was performing at a capacity where KIWASH did not deem a performance improvement plan warranted. Instead, with KIWASH support, KIWASCO itself became a “mentor” organization, pairing with two smaller providers—GULF and NYANAS. KIWASCO provided support and mentorship to the two utilities, improving their performance while they continued to operate independently. Under KIWASCO’s supervision, GULF and NYANAS saw a 19 percent and 16 percent decrease in non-revenue water, respectively, and they added more than 470 new water connections.

Across all the counties, the biggest technical challenges facing water service providers and small WASH enterprises were dilapidated infrastructure, poor operational and maintenance techniques, and ineffective asset management. Complementary to the internal strengthening and training KIWASH provided, the project facilitated improvements to locally prioritized infrastructure needs. Importantly, KIWASH paired its infrastructure support with technical and operational support to providers to ensure they can adequately manage expanded services, more customers, and a higher volume of billing and revenue collection. The pairing of technical, operational, and infrastructure programming resulted in new or improved water service delivery for 25,800 people in Kisumu, and 55,406 in Makueni.

Replication, Scalability, Sustainability

From the start, KIWASH was committed to locally developed and locally led solutions. Work with county governments laid a foundation for the sector during Kenya’s devolution and improved understanding of roles and responsibilities, ensuring these were codified in policy. Tailored support to water service providers and small WASH enterprises resulted in operational improvements and more financially efficient and viable businesses. Not only did these activities open doors to external financing, commercial or otherwise, but they also freed up domestic revenue to be used to support underserved, less financially viable areas.

Water service provider KIWASCO served as an example for other utilities. “One thing that I think we learned that works is that it is very critical to build the capacity of the smaller institutions by building on the experience that you have from the more successful, bigger institutions,” said Mbuvi. “The work that KIWASCO has been able to do in terms of mentoring the growth of others has been very critical. This is something that I think that we can replicate across the country.”

Complementing the success of capacity building carried out through existing institutions, KIWASH saw success in cross-utility knowledge-sharing networks, and exchange visits between water service providers and small WASH enterprises, which yielded productive benchmarking and joint planning efforts. In Kisumu, noting KIWASCO’s successes in improving customer relations and management systems, the project facilitated a learning exchange for staff from GWASCO to KIWASCO to learn good customer management skills, such as customer satisfaction and identification surveys, and the re-design of customer contracts.

Integrating women into KIWASH's programming was key. Photo: USAID KIWASH.

Filling the Gaps and Thriving

Prior to KIWASH, water service delivery in the partner counties was hampered by technical and operational gaps and weak policy management. Existing rules and regulations were not well defined and with the country’s decentralization of service delivery, responsibilities between stakeholders were not well understood. By the project’s close in 2021, KIWASH ensured that all nine counties’ policies and procedures were codified in law, and water service providers were performing at higher levels.

Through embedded staff, the project was seen as working with the community, and not outside of—or against—it. Basing project staff in target counties allowed for better coordination with, and support to, pre-existing WASH coordination platforms, which allowed KIWASH to leverage these spaces to engage in conversations around issues, challenges, and opportunities. “Always support county-led initiatives for the best success,” said Mbuvi.

As Kenya continues to develop its decentralized water service delivery systems, the following take-aways from KIWASH can help guide future programming:

- County governments still require support to strengthen their ability to adequately provide oversight to water service delivery. Major investments are needed to enhance the ability of county governments to improve regulatory authority. There is no replacement for good governance, so it is vital to get this right.

- Programs should support county-identified priorities and strategic plans, not enforce project activities or mandates onto county-level actors. It pays to take the time to understand county plans and goals, and to help implement their vision.

- Sustainability must be at the center of programming, and that entails coordination between actors early on to ensure that their joint efforts reinforce sustainability. KIWASH worked with stakeholders and development partners at the beginning of the program to map out which activities could be coordinated to show the effectiveness of overlaying interventions and to reduce replication.

- Programming to support the strengthening of water service providers and small WASH enterprises must meet providers where they are in terms of technical, financial, and operational capacity. Co-designed performance improvement plans can play a key role in strengthening smaller, less capable providers and systems.

Devin Nihill worked as a Global Practice Specialist for DAI’s Water Security, Sanitation, and Hygiene practice.