DEVELOPMENTS

Six Ways to Mitigate Instability in Central America

Feb 1, 2017

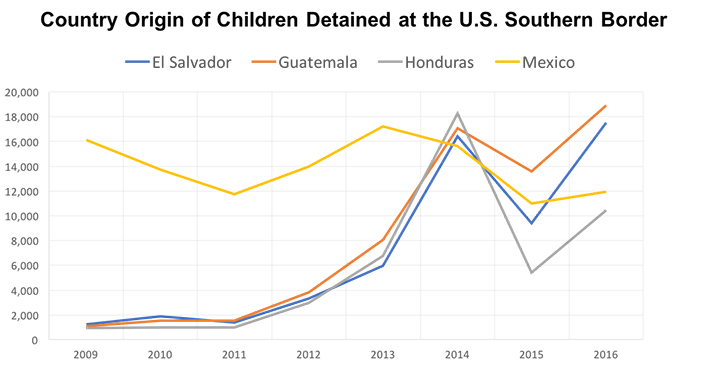

Some people might be surprised to know that most of the migrants trying to cross the U.S. southern border come not from Mexico but from countries to Mexico’s south.

Eighty percent of the unaccompanied child migrants detained at the border in the year ending September 2016—roughly 47,000 out of 59,000—came from Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. Migration from these “Northern Triangle” countries has spiked since 2013, with many migrants forced from their homes because their families are impoverished, their communities overrun by gangs, and their countries’ governments ill-equipped to fix such problems.

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection

But these conditions are not beyond our influence. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and other donors are working with local partners to gradually help make Central America’s communities more livable, building on empirical studies that are yielding important insights into what interventions are working and why.

America’s support is indeed “getting results” and reducing migration, James D. Nealon, the U.S. Ambassador to Honduras, told the New York Times in 2016. “It’s not charity,” said Nealon, who believes that if the United States can sustain its anti-violence work in Honduras, “in five years they will get their country back.”

DAI’s own portfolio illustrates half a dozen ways in which ongoing assistance in economic growth, workforce development, rule of law, governance, and other areas is delivering increments of stability in these critical countries.

1. Helping Central American Countries to Help Themselves

More than ever, emerging nations are seeking to fund their own development agendas. USAID and other donors have pledged by 2020 to double assistance designed to help developing countries mobilize their own resources. When successful, assistance for domestic resource mobilization yields an extraordinary return on investment, as in El Salvador.

From 2004 to 2011, the Government of El Salvador raised an average of more than $300 million annually in additional tax revenue—without raising tax rates. How? Programs funded by USAID and implemented by DAI helped the government establish policies and systems that resulted in more people paying taxes and fewer earners falling through the cracks.

Among other results, this cash influx enabled the government to increase health spending per capita from $93 to $142, while citizens’ out-of-pocket health expenses fell from nearly $100 to $61 per capita. By 2013, 164 of the country’s 262 municipalities—many of them poor and rural—delivered expanded access to basic health services benefitting 1.9 million Salvadorans.

More recently, USAID’s assistance has helped El Salvador to implement a Single Treasury Account, which consolidated 1,600 government bank accounts, recovered idle balances totaling $25 million monthly, and reduced vendor payment transaction times from 10 days to a few hours. The new e-procurement system COMPRASAL II facilitates greater transparency and efficiency in public procurement.

El Salvador’s development plan calls for more domestic investment in education and citizen security alongside an evolving strategy to address the country’s debt. Alert to El Salvador’s successful fiscal reform, neighboring Guatemala has recently launched a similar process under USAID, implemented by DAI, to reduce debt and increase revenues and expenditures for much-needed services.

2. Helping Young People Find Work

More than one million young people in the Northern Triangle are neither in school nor employed, according to UNICEF, including 350,000 in Guatemala and 240,000 in El Salvador. In Honduras, 27.5 percent of youth neither study nor work—known as ninis, for ni estudian, ni trabajan—the highest rate in Latin America.

Young people in the Northern Triangle face a daunting employment landscape. In July 2016, USAID/El Salvador launched Puentes para el Empleo, the Bridges to Employment program. A five-year activity, “Bridges” is laying the groundwork to accelerate the hiring of at-risk youth. The Bridges team and local partners are developing a national database that details what workers are in demand and where; the data will also be used to drive training and employment services to meet the skills gap.

Focusing on 50 Salvadoran municipalities, Bridges has already trained hundreds of at-risk youth—and will ultimately train 20,000—to improve soft skills such as teamwork and problem solving, as well as vocational skills in growth areas such as plastics, information technology, and service industries so these youth can more effectively integrate into the workforce.

Similarly, the USAID Nexos Locales project in Guatemala is bringing together young people and their local governments to work on local policies and programs for improving lives in the Western Highlands.

3. Supporting the Justice Sector and Community Police

Fueling the exodus of children, teens, and young adults are local gangs such as MS-13 and Barrio 18. These gangs emerged in Honduras in the late 1990s after U.S. legislation increased deportation of ex-convicts; they are in a growing battle for territorial control, putting Honduran communities on the front line of this struggle. Complicating the situation, an estimated 95 percent of crimes go unpunished in the Northern Triangle, with homicide rates far exceeding those in Mexico, making it one of “the most murderous places on Earth.” Unsurprisingly, communities with a prevalence of gang violence suffer from stunted economic activity and job creation.

USAID recently launched the five-year Unidos por la Justicia (United for Justice) program in Honduras. This work aims to increase the effectiveness and engagement of local police departments and courts, where systemic failings perpetuate high levels of crime and impunity.

“Unidos por la Justicia seeks to help stabilize these vulnerable communities by ultimately reducing impunity and the pressures to migrate or join gangs,” said Shanna Tova O’Reilly, a senior global practice specialist in DAI’s Governance sector.

Complementing this work, USAID recently launched the five-year Honduras Local Governance Activity, which will assist 80 local governments in western Honduras to boost public service delivery. This collaboration with mayors, city councils, citizen groups, and municipal and state agencies will help previously marginalized communities gain better access to education, health care, and essential infrastructure.

4. Creating Jobs and Growth by Managing Natural Resources

Honduras’ rich forest and marine resources belie its struggling rural economy. In 2011, DAI launched USAID Honduras ProParque to spark economic growth by aligning natural resource management with sustainable economic growth. ProParque had a significant impact: creating more than 5,000 jobs in sectors such as coffee, cocao, and tourism; mobilizing $9 million-plus in private sector investment; and facilitating $13.3 million in new sales by small businesses—while simultaneously improving the conservation of 350,000 hectares of critical ecosystems.

This new economic activity arose because the ProParque team worked side-by-side with the government, private sector, and citizens to protect essential natural resources such as water while leveraging their economic value in areas such as tourism and forestry. ProParque trained 111 micro-entrepreneurs on improving rural access to clean and renewable energy, for example, and these small businesses in turn outfitted 25,000 people with clean cook stoves, solar panels, and bio-digesters.

ProParque also assisted the Honduran government in improving land and water policy and the management and governance of the national protected area system, which covers nearly 22 percent of the national territory.

Encouragingly, ProParque emerged as a stabilizing force at a village and municipal level, with local government units and the private sector noticeably collaborating and working toward a common vision of economic growth and conservation. USAID and DAI are building on the momentum of ProParque under a new five-year project—Governance of Ecosystems, Livelihoods, and Water—that aims to further enable Honduran communities to achieve long-term economic growth.

5. Helping the Coffee Sector Adapt to Damaging Climate Conditions

Northern Triangle countries rank at or near the top of the Global Climate Risk Index, which measures deaths and economic losses from climate-related events. From 2014 to 2016, severe drought led to crop failures, hunger, and damaged livelihoods for more than 2.8 million people, hitting especially hard in the “dry corridor” from southern Mexico to northern Costa Rica. In addition to alternating droughts and floods—the latter washing away baked topsoil and surviving crops—forecasts call for higher temperatures and disruption to the water cycles that determine rainwater, groundwater, and freshwater supply.

This extreme weather deeply affects the millions of Central Americans who depend on the coffee sector for their livelihoods. This mostly high-quality, specialty coffee is vulnerable to coffee rust, a devastating fungus that flourishes in the warmer, damper conditions associated with a changing climate.

In collaboration with NASA and the NASA Space Apps Challenge, the Central America Regional Climate Change Project—funded by USAID and implemented by CATIE, DAI, and others—worked with Costa Rican youth to create the “Coffee Cloud” mobile app and platform. The Coffee Cloud app centralizes and disseminates information around daily and seasonal forecasting for coffee crops and reports outbreaks of diseases so that growers and governments can take action. Large coffee institutes led by Promecafe have accepted the Coffee Cloud as their official tool to respond to coffee rust throughout the region.

“Just like almost everywhere, young people in the Northern Triangle are avid users of new technology,” said DAI’s Adam Fivenson, an information and communication technology (ICT) specialist who works in the region. “Looking at it from an ecosystem perspective, we haven’t seen the high levels of financial or institutional support for using ICTs in addressing development challenges in Latin America.

“We see our role as ‘sourcing local innovation,’ which means we are involving local young people in the design process from idea generation to coding to community engagement. That’s the story of Coffee Cloud, and later this year we are planning to start the process again with a design-thinking workshop with NASA, followed by a public design challenge.”

6. Boosting Agricultural Trade in the Region

To help farm communities prosper by means of intraregional trade and exports, the four-year USAID Regional Trade and Market Alliances (RTMA) project supported rural producer associations in Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, and Nicaragua.

Working as a subcontractor to Nathan Associates, DAI assisted producers of potatoes, beans, onions, and other crops to upgrade their equipment and operations. RTMA identified the most promising value chains for regional trade and worked with 40 producer organizations to improve their regional trade relationships. More than 6,000 producers were assisted, with many increasing the quality and standards of their produce, securing better prices, and increasing income and employment. Additionally, $6.2 million was invested in grants, resulting in increased sales of $9 million by beneficiaries now better equipped to enjoy sustained economic success and create jobs. The value chain grant recipients are largely producer associations, 10 of which are projected to increase exports by an average of 76 percent by the end of the grant.

A More Livable Future

Every day, too many citizens in the Northern Triangle face the decision of whether to remain in their homes or look outward to what they hope is a better life. But with USAID’s support, the governments of El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala are increasingly determined to strengthen the institutions responsible for delivering fiscal stability, economic growth, and citizen security.

Various studies and our own experience in the Northern Triangle have shown the value of directly targeting at-risk communities and including gang members in programming, of taking a proactive approach and staying ahead of violence rather than reacting to it, and of partnering with local authorities and institutions with a view to long-term sustainability. We look forward to applying these and other lessons as we seek to assist the governments and the people of the region in their quest to build more prosperous and more stable communities.