DEVELOPMENTS

Q&A: Unlocking Inclusive Economic Growth for Mozambicans by Building a Market for Digital Financial Inclusion

Sep 8, 2017

While Mozambique’s economy is emerging—notably through the extractives sector—most Mozambicans remain very poor. Eighty percent still make a living from subsistence farming. One cause for their marginalization is that most have no connection to the wider economy or to basic financial services such as saving, borrowing, and electronic payments. This limits the ability of Mozambique’s 12 million rural poor to grow their livelihoods and perpetuates their isolation and poverty.

Launched in 2014, the Financial Sector Deepening Moçambique (FSDMoç) project is working to create access to financial services for at least 2.6 million households and 1,000 small and growing businesses. This access will enable Mozambique’s households and enterprises to use responsibly delivered finance to pay for seed and fertilizer, pay electronically for necessities such as medicine, and safely deposit their savings, among other benefits. Banking electronically and with mobile phones will reduce the time, cost, and risk associated with transacting in cash only.

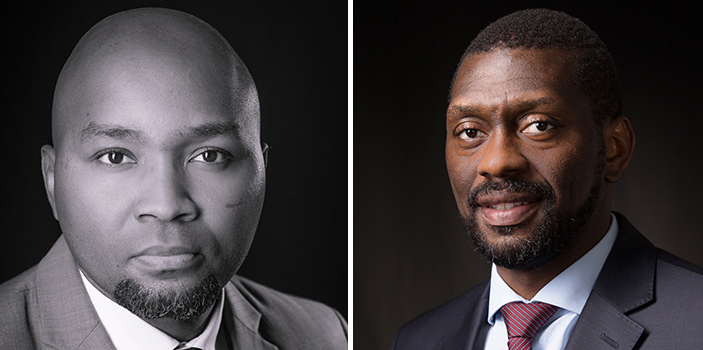

FSDMoç is funded by the U.K. Department for International Development and Swedish International Development Agency. Developments recently discussed FSDMoç with two members of its Maputo-based team—Investment Manager Benedito Murambire, below right, who develops private sector investments that support financial inclusion, and Market Development Manager Helder Buvana, below left, who focuses on investments in agribusiness and financial technology.

How common is mobile technology in Mozambicans’ daily lives, and where do you see it going?

Benedito: Mobile technology covers 82 percent of the population, but internet usage has not picked up at the same rate. Of those with coverage, 94 percent have used mobile phones for voice and 84 percent for text messaging. Thirty-one and 32 percent, respectively, have sent and received money, but only 23 percent have used social media, indicating low overall internet usage.

On the plus side, the cost of 1 gigabyte of mobile broadband data in Mozambique is US$2.80, which compares favorably with, for example, neighboring Malawi at US$5.80. This lower cost provides opportunities for digital, including in financial services. But the use of cash still predominates, especially in rural districts. People are understandibly hesitant to try new things where their money is concerned.

What will drive growth in digital financial services?

Benedito: Need and demand, which are plentiful. Remittances now drive services via Vodacom Mpesa, Zoona, or the mobile wallets of six different banks, but other needs are emerging. In addition to buying farm and household goods and services electronically, people would pay their insurance premiums, taxes, and fees that way, and government employees such as teachers and nurses would receive their salaries. Drought victims and others could receive e-vouchers for emergency and disaster relief.

Helder: While remittances now drive mobile money, down the road electronic transactions will not simply be led by telecoms and banks—other payment platforms will adapt, such as retailers, petrol stations, and agro-dealers.

Why do people with little or no money need to have access to digital financial services?

Benedito: Financial inclusion is about more than inclusion. Currently, the “unbanked” have to carry their cash, use their time, and travel to pay in person for everything—insurance, health care, water bills. Through its private sector partners, FSDMoç is facilitating better living by saving them the time and expense—and reducing the risk—posed by living cash only. People in developed countries, such as our donors in the United Kingdom and Sweden, are accustomed to saving time, seeking out convenience, and decreasing risk. FSDMoç is striving to deliver these same benefits for Mozambicans, and they do not need a lot of money to benefit. Eventually, all smallholders, households, shops, merchants, financial services providers, mobile network operators, and local government services will be connected and efficiencies will be gained.

Helder: This includes scaling up through agricultural value chains, which FSDMoç is doing, so that all members are connected digitally. We are currently working in Mozambique’s cotton value chain trying to connect all of its actors digitally—from small-scale cotton producers to transporters to storage operators to exporters. This helps expedite payments back and forth while creating better data and records and opening up crossborder transactions and trade.

What approach has FSDMoç taken to expand digital financial services?

Helder: We work with multiple partners to influence Mozambique’s digital ecosystem. These include mobile network operators wishing to expand beyond cities, commercial banks developing safer loan products for rural borrowers—such as for solar home systems—and government agencies that need complementarity in their regulations, and so on.

It is also important that we promote the innovation and new ideas required to connect these dots and make them work. In April, FSDMoç conducted the FinTech Challenge, where we received 22 applications from financial tech companies, with seven shortlisted to receive technical assistance from the FSDMoç team and £5,000 each. One of the winners is providing an accounting-based app for small and medium enterprises, for example, and another an app to help informal savings groups (known as xitiques).

What are some of the more promising trends and opportunities?

Benedito: Once there is a scalable digital ecosystem in Mozambique, we can expect electronic payment of premiums and claims for health or crop insurance, and the purchase of incremental construction materials for basic housing. This will materialize once there are ample digital transaction pools. In other words, once there is enough of a digital float in the system that enables cashing in and out of the system without delays.

We also see ways in the short term to apply digital capabilities to benefit existing “bottom of the pyramid” local activities. This includes enabling groups to take out group loans with banks to buy seed and fertilizer, for example, and also to make group deposits.

Considering the magnitude of challenges faced by Mozambique’s poor, financial inclusion will only be sustainable if banks see the value of complementarity with financial tech or vice versa. If the banks play their cards right, they have access to a much larger client and partner base. If they act like a cartel, they will not gain access to a larger market.

The success of mobile money in the region has generated a lot of news. What is the headline from Mozambique?

Helder: If we can increase the interoperability between users and suppliers at all levels, that will boost mobile money and payment channels, bring down transaction costs, and create a network effect. This is where the financial tech firms come in—to provide solutions and services that make mobile money and e-payments work better, and that make local financial institutions work better. For example, financial tech firms can develop software applications that help in logistics by facilitating payments between businesses and suppliers. Financial tech firms are the missing players in the system—as they emerge and grow, they will increasingly contribute to and help connect Mozambique’s fuller suite of digital services.

Benedito: We are working with the Banco de Moçambique (Central Bank) and the National Institute of Communications to enable and encourage financial tech firms to operate and help make the digital finance ecosystem more attractive and relevant for users. We plan to organise a supportive environment to incubate financial tech firms and create a “sandbox” approach where technology innovators are safe to test, learn, and collaborate with financial service operators.