DEVELOPMENTS

Supporting Women’s Inclusion Through Community Development in Pakistan

Mar 8, 2021

Since the early 2000s, the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), home to more than 30 million citizens in northwest Pakistan, has suffered from the effects of militancy and natural disasters. Taliban attacks from neighbouring Afghanistan and severe droughts and floods have displaced people, increased poverty, hindered access to basic services, and sown distrust in government.

To tackle these issues, the Government of KP launched a Community-Driven Local Development (CDLD) policy in 2013, providing people with the opportunity to access public funds and use these resources to address their local development needs. For more than six years, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa District Governance and Community Development Programme (KP-CDLD), fueled by budget support provided by the European Union (EU), helped to implement this policy, working to restore citizen trust and generate livelihood opportunities while at the same time promoting women’s inclusion in this highly traditional and patriarchal society.

Supporting a Complex Programme

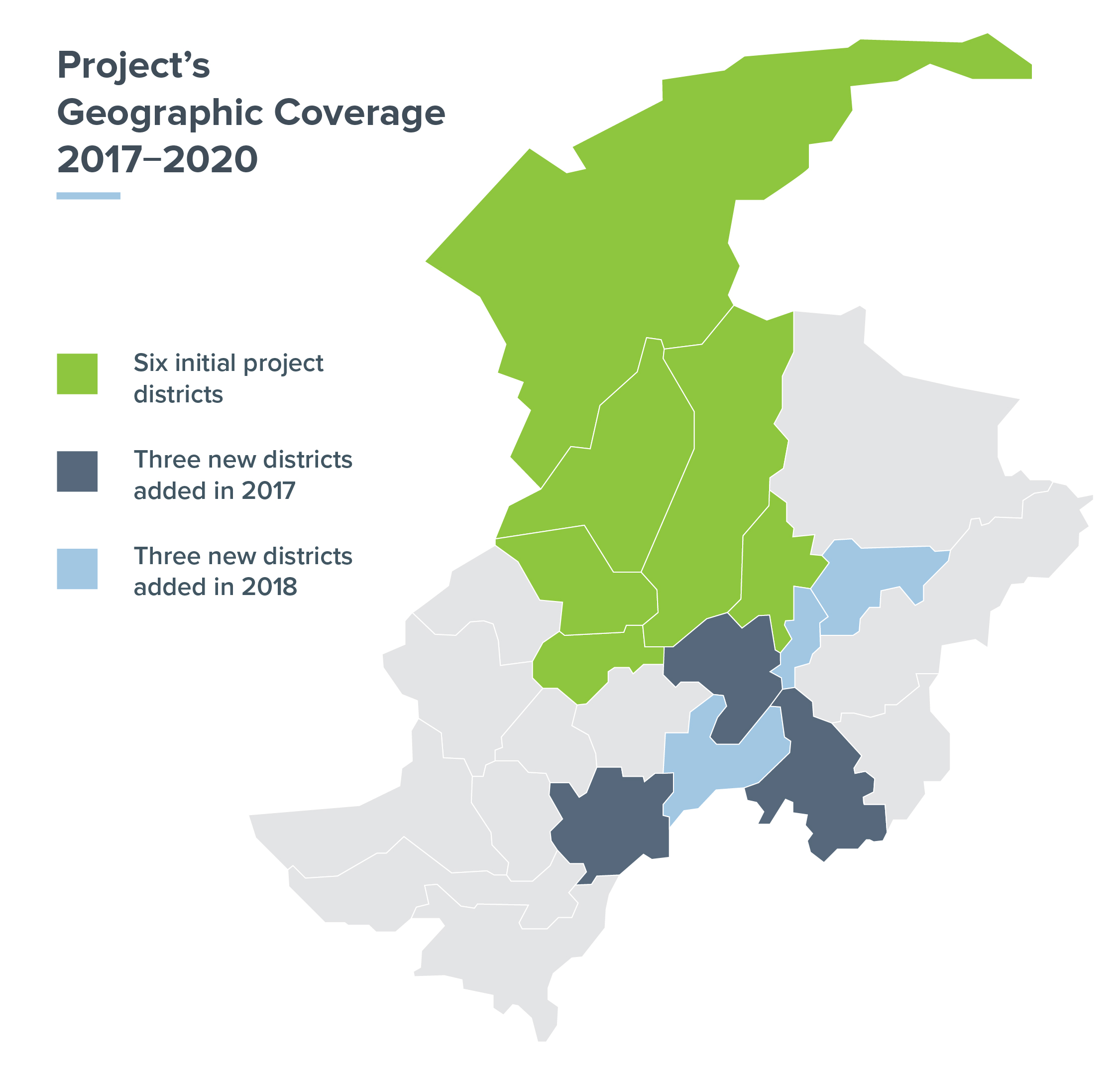

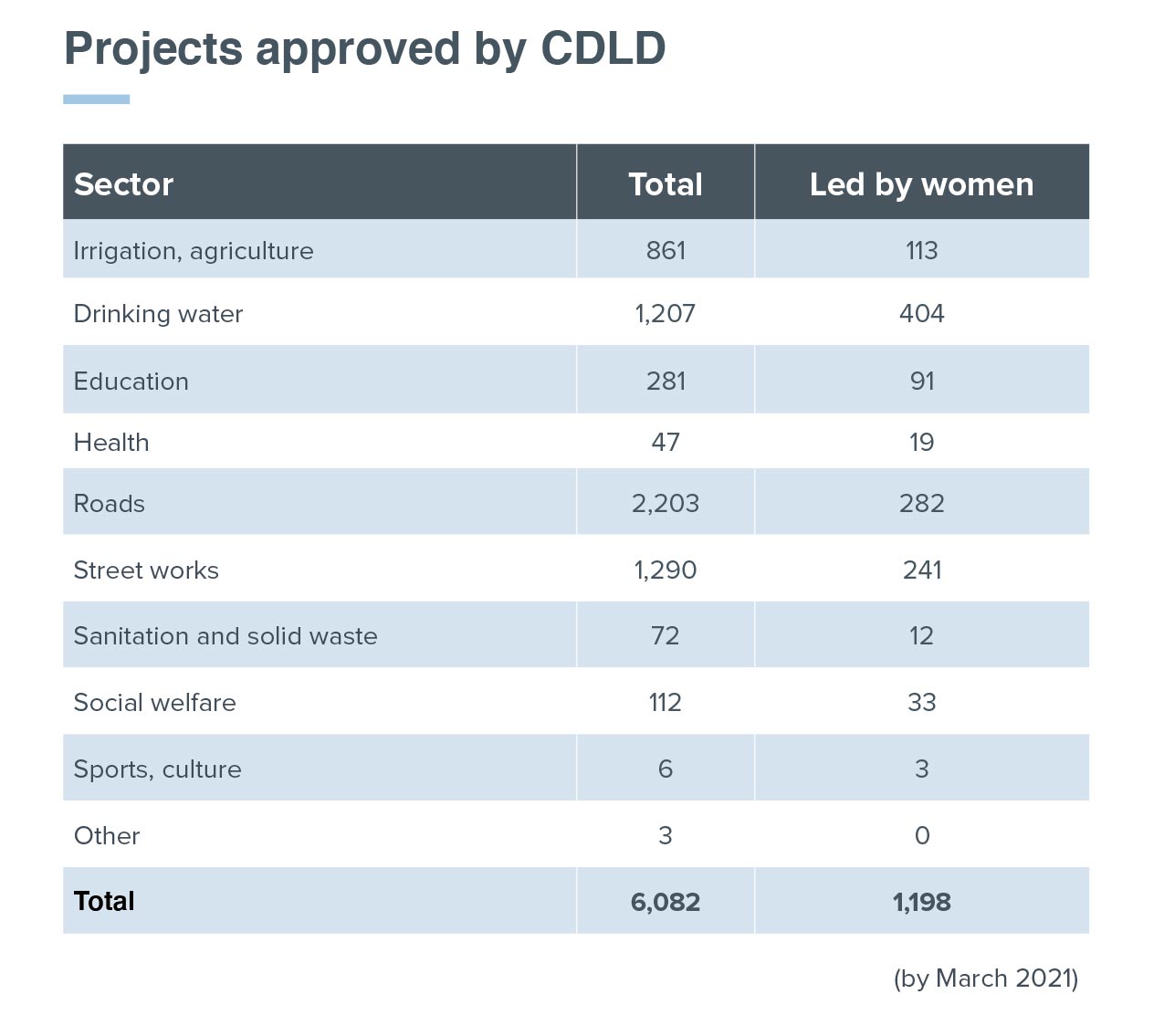

The CDLD policy established the institutional framework for the formulation and approval of local development projects. Over six years, through meticulous social mobilisation, capacity building, and awareness raising, a team—led by Human Dynamics, which was acquired by DAI in 2019—supported vulnerable rural communities and marginalised households in 13 districts, ultimately seeing 4,718 out of the 6,006 approved projects through to completion before the close of the project in 2020—19 percent of these projects led by women.

In the target community, access to basic services improved as a result of the KP-CDLD Programme, particularly access to drinking water, education, health, sanitation, and livelihood opportunities. For example, in June 2015, only 25 percent of households lived above the poverty line, according to surveys conducted by the project team; by December 2017, that number had risen to 37 percent. Access to water increased from 52 percent to 60 percent in the same period, and some 400,000 people benefited from diversification in on-farm and off-farm enterprises. Gender sensitisation was a common theme across these activities.

Supporting the identification, formulation, and implementation of such a large number and variety of projects called for a highly structured approach to technical assistance. Senior experts managed teams at the provincial and district levels to cover capacity building, policy advice, communications, engineering, and other topics. Teams of four experts (a coordinator, field engineer, project cycle management/capacity building specialist, and monitoring and evaluation specialist) were deployed in each district.

“At one point, we maintained 15 project offices, had 18 vehicles running, and 100 consultants—plus 35 support staff,” said Holger Hinterthuer, DAI’s Director for this project, recalling the complexity and scale of the project management challenge.

The team embraced its capacity building mandate. “Capacity building of local governments ensures that once the technical assistance contract ends, [our counterparts] can continue to implement the activities initiated during the project, with the government looking after the construction projects,” said Tehmina Kazmi, who led KP-CDLD’s capacity building and gender mainstreaming efforts.

DAI’s team delivered 246 training sessions for nearly 6,500 government officials and representatives of village councils, complemented by 5,000 sessions of on-the-job technical assistance reaching more than 7,200 personnel. Courses included engineering standards, management information systems, monitoring and evaluation, grant management, communication, social mobilisation, and gender sensitisation.

“When conducting gender sensitisation trainings for government official staff, we never gave them lectures or big sermons about women’s participation,” Kazmi said. “But, with little exercises and games, we made them realise that women are contributing a lot, and that with the support of the project, they can contribute even more.”

The EU-funded project ensured women's voices were included in all activities. Photo: EU KP-CDLD.

Incentivising Change

In the traditional communities targeted by the project, some run according to the tenets of Sharia Law, women do not have much control over their lives. They have limited mobility outside of their villages and their needs are seldom considered in the design and construction of public premises. Consequently, girls in such communities typically stop going to school during the rainy season because their clothing restricts them from walking on muddy roads; women and girls often lack healthcare because health centres do not allow for privacy; and women do not engage in business or livelihood activities.

To boost the inclusion of women and help change the mindsets of local communities, the Government of KP and the EU required that 25 percent of the CDLD-funded projects should be led by the community’s women. This meant a potential loss of 25 percent of the money allocated to a community’s development if women did not initiate and manage these projects.

Despite this strong financial incentive, “There were hardly any women’s projects in the first two years of implementation,” according to Kazmi. DAI’s team insisted on better integrating women into the process and “led the government to hire women social mobilisers and female facilitation officers to encourage women to apply for the projects,” said Kazmi.

Mobilising Communities

Getting buy-in from local communities was key to KP-CDLD’s success. Efforts to win people over included forming and training community-based organisations, and having them take the lead in identifying, planning, implementing, and managing the small infrastructure projects.

Bridges like the above were part of the infrastructure projects chosen and implemented by communities. Photo: EU KP-CDLD.

After a couple of years of implementation, with the hiring and training of women social mobilisers and the support of government employees and female elected representatives, the project began to hit its inclusion targets. Government officials went to the communities and made the case with local men for women’s participation: “We talked to husbands, brothers, fathers,” Kazmi said. “We explained the aims and objectives, what we want to contribute.”

Eventually, out of the 5,600 organisations formed during the project, 1,114 were women-only. These groups identified, designed, and managed local development projects that responded to their own needs. By the end of the project, there were actually more women-led projects than anticipated in the budget.

Women social mobilisers played a key role in the turnaround. They became role models in their villages—inspiring women to get together and consider their common interests.

No doubt restrictions on women’s participation and inclusion will persist to some degree, but the KP-CDLD programme has shown the way forward. The CDLD community-based development policy is now officially recognised by the KP Government as its “signature gender-sensitive social delivery programme.”

Mathilde Gaston-Mathé and Elizabeth Drachman are Senior Communications Specialists at DAI.