DEVELOPMENTS

Working Together? We’re Working On It

Apr 1, 2015

For DAI, one of the great advantages of implementing an extensive and diverse group of projects is the opportunity it affords us to learn and collaborate across a multiclient portfolio—to bring insights from U.K Department for International Development (DFID) programming into our U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) work, for example, and vice versa; or to coordinate mutually beneficial activities that cross project and client lines.

We do not take the challenge of collaboration lightly. We know that collaboration doesn’t necessarily happen by itself and coordinating the work of multiple projects can be difficult, even within the same client set. We know that “organizations don’t collaborate, people do”—and that people must be incentivized, situated, and enabled to work collaboratively if we expect them to go beyond the contractually stipulated responsibilities of their individual projects.

But in various parts of the world, DAI now has the kind of connectivity and critical mass where these favorable conditions are coming together. In East Africa, for instance, we are implementing a significant number of projects funded by USAID, DFID, the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, and the European Commission. In Kenya alone we manage the activities of seven major projects—three for USAID, four for DFID—and Nairobi serves as the head office for another USAID project focused on Somalia.

It was in Nairobi, on February 18 and 19, that we convened 25 people and seven DAI-managed projects from East Africa to explore how we might better foster collaboration, with the aim of improving programming, delivering greater value to clients, and minimizing the risk of missed development opportunities. Some of the lessons we took from our two-day workshop might help other practitioners get the most out of similar portfolios.

Getting the Basics: Who, What, Where

For our first workshop session, each project team put together a poster focused on the three things you really need to know if you’re looking for synergies: the key project initiatives, the principal project partners, and the geography and the population where and with whom the project is engaged, at the most granular level possible. As each project presented, the other projects noted their ideas for collaboration.

Building on these initial ideas, the second session took a “deep dive” into areas that offer tangible opportunities for strategic collaboration. Seed quality is one example. Among smallholder farmers in the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) region, fewer than one in four have access to high-quality seed, a state of affairs that exacerbates poverty and food insecurity. DAI projects are already working together to support COMESA’s efforts to harmonize regional seed trade policies and align them with domestic, national approaches, thereby improving the availability of high-quality seed. Africa Lead helped COMESA develop its Seed Harmonization Implementation Plan (COM-SHIP), and three DAI projects are now working to operationalize it: Africa Lead, developing seed information systems; FoodTrade ESA, compiling a regional seed variety catalogue; and FoodTrade ESA and the East Africa Trade and Investment Hub, assisting national governments and other stakeholders to implement COM-SHIP policies, regulations, and programs. All three projects are part of a concerted effort to raise awareness of COM-SHIP among regional regulators and private sector associations.

Workshop participants reaffirmed their commitment to enrich this collaborative process in ways that should yield economies of scale for the donors while ensuring cohesive program design and execution across various levels of government in the region.

Collaboration “Pain Points”

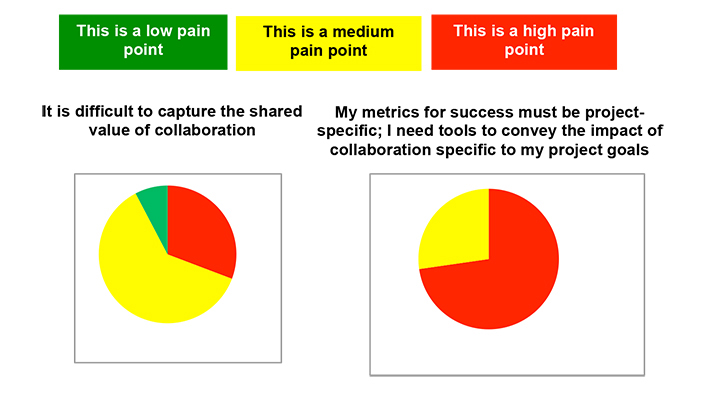

Articulating the value of such collaboration, particularly its value to the client, was the focus of our third session. This emphasis turned out to be prescient, because in our fourth and final session, where we addressed factors limiting our ability to work together, we found that the biggest obstacle is the absence of metrics to quantify the impact of collaboration, especially in the context of project-specific goals. In this session, we asked participants to rank collaboration “pain points” as low, medium, or high.

Combined with participants’ perception that clients don’t necessarily allocate sufficient time and resources for cross-project collaboration, it became clear that developing metrics credible to donor funding agencies will be an important exercise. We have an idea of what those metrics will look like—time saved; new, improved, and replicable approaches generated; greater potential for attracting additional funding from new sources; reduced risk; smarter partnerships; enhanced sustainability; better value for money; deeper and broader development impact—but making a quantifiable case for collaboration remains a work in progress.

Key Recommendations

Developing metrics to understand and convey the “additionality” of working together is one of the recommendations emerging from the workshop. The others:

- Facilitate Networking: DAI should sponsor more frequent regional meetings (formal and informal), and set aside time for staff from different projects to interact. We already have our next East Africa meeting scheduled for mid-April.

- Improve Access to Information: Accurate, relevant, and timely information must be readily available on the company intranet, and actively distributed to key audiences.

- Enhance Support from Headquarters: Project directors in the corporate offices must have the incentives and bandwidth to engage with projects outside their scope, and collaboration opportunities should inform travel itineraries.

- Recruit, Train, and Manage Appropriately: We must instill a collaborative ethos in projects from the outset—that means selecting team leaders with the right personality traits, making sure that collaboration is prioritized in kickoff meetings and workplanning, and ensuring that information sharing is written into someone’s scope of work.

Finally, and perhaps ironically in light of the fact that we spent two whole days focused intently on ways to enhance collaboration, a strong consensus held that we cannot force collaboration and should not over-engineer it. The collaborative impulse flourishes where it is organic and clearly adds value for each project team and its client; it flounders when it becomes a collaboration imperative. Our job is to create a culture conducive to good behavior, which means an environment characterized by good information channels connecting like-minded actors who have mutually reinforcing objectives. The Nairobi workshop was a fine example of that kind of environment, and one we intend to replicate wherever we can.