Afghan Farmers Borrowing Money for the First Time, Investing in Their Livelihoods

Aug 26, 2012

Agriculture is Afghanistan’s lifeblood. Making agriculture work better means putting more food on the tables and more money in the pockets of Afghan farmers—and of everyone connected to farming. The Agricultural Credit Enhancement (ACE) program enables those who make agriculture work to borrow money locally, invest in basic inputs such as seed and fertilizer, and repay the loans after their crops come in.

In the West, where almost anyone can borrow money, we take credit like this for granted. But in Afghanistan, and especially to rural farmers and related businesses, credit is alien. ACE is filling this gap. In the past year, the project has facilitated credit for more than 15,000 rural households. And because these loans are channeled through the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, the borrowers increasingly feel that the government is engaged on their behalf, making the project a valuable complement to other programs designed to nurture public support for the institutions of governance.

The Agricultural Development Fund is fully operational, with approximately 70 employees, a central office in Kabul, regional offices in Jalalabad, Mazar-e-Sharif, and Herat, and a provincial office in Bamyan. Through this infrastructure, the fund has lent some 1.5 billion Afghanis, or about US$37 million, directly benefiting 15,000 rural households in 25 of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces.

Perhaps most importantly, these basic and affordable loans are being repaid diligently. Indeed, the future appears bright for this new financial service and its beneficiaries.

Underestimating The Challenge

The high-profile, five-year ACE project is funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). At its heart is the Agricultural Development Fund (ADF), a US$100 million loan fund that DAI co-manages with the Afghan Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation, and Livestock. In fact, our main office is housed within the Ministry. From its onset, we expected ACE to be challenging because of the ambitious targets laid out by our client as well as the hesitation of Afghanistan’s banks to lend to agriculture. ACE also marked one of USAID’s first attempts to work directly with the Afghan government. If anything, we underestimated this challenge. Not a single day has gone by in which ACE hasn’t had to come up with creative and innovative ways to overcome what seems to be an endless chain of obstacles.

The ACE/ADF loan program set out to work mainly through financial intermediaries such as banks and non-bank financial institutions, and to a lesser extent through nonfinancial intermediaries and agribusinesses. A few months into the project, we realized the implementation environment was substantially different from what was originally thought. We had designed ACE based on five fundamental assumptions, most of which were somewhat flawed:

- At the right price, commercial banks and other financial institutions will engage in agricultural lending. The flaw: The risk faced by Afghan financial institutions transcends those of a weak institutional environment, high transaction costs, and obstacles to contract enforcement. With many banks on the verge of closure due to high portfolios at risk, risk aversion made the “right price” for lending prohibitively high.

- ACE will provide large loans to financial and non-financial institutions, and a very small number of direct loans to agribusinesses. The flaw: The unwillingness of the financial sector forced ACE to rely heavily on nonfinancial institutions with no experience in credit management; this approach spurred us to make a series of innovations to build the capacity of such institutions to execute their credit management activities in a way that ensures the repayment of loans.

- The government will register the Agricultural Development Fund in the months following the inception of the project. The flaw: The ADF was finally registered 18 months after the inception of the project; meanwhile, we had to take risks beyond the norm in order to deliver results in an environment of ubiquitous adversity and uncertainty.

- Innovation grants will encourage financial institutions to design and launch Sharia-compliant financial products. The flaw: In the absence of financial institutions interested in on-lending ADF funds, and in an environment where nonfinancial intermediaries are unwilling to make conventional loans, we had to “teach ourselves” and create in-house capacity for the development of Sharia financial products.

- The Afghan Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Livestock, where the ADF is housed, and USAID will maintain a close relationship that will facilitate the implementation of the project. The flaw: Both the Ministry and USAID have been supportive, but serving two masters has proven challenging, especially considering that Afghanistan remains a politically charged environment. Internal government politics, numerous and diverse agendas, and pressure to disburse large amounts of money in a short time—while keeping a portfolio at risk below 5 percent—are just a few of the forces at play.

In the face of these challenges, we decided to make a sharp strategic shift by designing a set of innovations to manage the risk of working with nonfinancial intermediaries; namely, developing in-house talent in Islamic finance and adapting existing Sharia-compliant financial products to the specifics of Afghan agriculture, all while rolling out an aggressive credit program.

Innovation 1-Credit Management Units (CMUS)

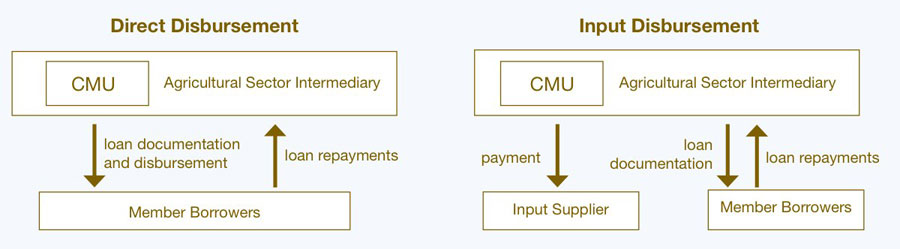

CMUs are teams of three to six local finance and administration personnel. They are located within the nonfinancial organization that is serving as a financial intermediary, typically a cooperative or farmer association. While CMU personnel report to the host organization, they constitute, in practice, a branch of the ADF.

These teams have three objectives: a) process on-lending applications submitted to the financial intermediary, b) administer the loan portfolio, and c) ensure the timely collection of loans. ACE has a CMU Coordination Unit that monitors loan performance and alerts other project units at the first indication of complications.

CMUs are equipped with standalone portfolio management software and basic hardware that provide ACE with periodic reports. The costs of the CMU—software, hardware, and personnel—are covered through a grant for the duration of the loan.

Typically, the financial intermediary will keep a share of the “spread,” or markup (see Innovation 2 below). This markup is expected to cover the costs of the CMU once the lending relationship with ACE/ADF ends, enabling the future, locally owned and operated CMU to continue administering loans for the financial intermediary which, now with a positive credit history, becomes eligible for loans from the Afghan banking sector.

Currently, more than 4,800 farmers are serviced by five CMUs established within farmer associations and cooperatives. These CMUs manage more than $6 million and maintain a zero default rate.

Innovation 2-Islamic Finance

Three issues prevented ACE/ADF from lending at a pace consistent with the expectations of the Afghan government and USAID:

- The unwillingness of financial institutions to engage in agricultural lending, and consequently to design innovative Sharia-compliant lending products, as was originally planned.

- The absence of experience in Islamic finance applied to agriculture and agro-processing.

- A pervasive demand from prospective clients for Sharia-compliant loans, which Afghan providers were not equipped to supply.

Clearly, we had to innovate. So we adapted Islamic financial products commonly applied to sectors other than agriculture. Given the absence of legislation regarding Islamic finance in Afghanistan, as well as the need to keep the structure of financial products and administration of loans simple and transparent, ACE relied heavily on Murabahah, one of the simplest and most common Sharia-compliant lending mechanisms.

The ACE program has launched several initiatives to enhance agricultural livelihoods: a financial product exclusively for women agribusiness entrepreneurs and an interactive database that incorporates market data for over 50 agricultural commodities, as well as studies and other information related to Afghan agriculture. ACE also provides technical assistance to its clients, which includes training in financial management, crop production, market development, and other skills.

Typically, Murabahah is used in transactions related to the purchase of real estate, vehicles, machinery, and consumer goods. Essentially, it adds a markup to the original price of the good, which is not directly related to the time value of money (interest). Two examples:

- ACE/ADF lent $500,000 to the Eastern Region Farmer Association in Nangarhar province to buy fertilizer, which the organization would then sell to eligible members on credit. ACE and the association determined a markup for the fertilizer consistent with the typical market rate applied by agro-input dealers in credit sales. They then agreed the markup would be shared between the association and the ADF. In this case, the association would keep 20 percent of the markup and ACE would keep 80 percent. This markup-sharing Murabahah agreement translated to approximately 5.3 percent per annum. This effort was complemented through the establishment of a CMU to administer the loan.

- We made a loan for $2 million to the Said Jamal Flour Mill based on a Murabahah profit-sharing agreement. This loan was based on the estimated profit to be generated by application of the loan funds, half of which was to be used to procure wheat from wholesale suppliers while the other $1 million was to be on-lent to 1,200 farmers using a Salam agreement consistent with advances as part of production contracts. Following the estimation, it was agreed that the ADF would be entitled to 10 percent of the profit and the borrower (that is, the on-lender) to 90 percent. Translated, the ADF would actually be charging the borrower 6 percent per annum.

What Is Special About These Agreements?

- Both loans comply with Sharia principles at all levels, since both loans—from the ADF to the intermediary and from the intermediary to the end borrowers—comply with Islamic norms.

- The products are simple to design, track, and enforce, thereby reducing unneccesary uncertainty, which itself is a prohibition in Islamic finance.

- The ADF shares the profit with the borrower, but not the potential losses, which in the case of failure of the enterprise relieves neither the intermediary nor the end borrower from the responsibility to pay back the principal.

We have since drafted our Islamic Finance Policies and Procedures, which are being reviewed by the ADF advisory board. We are also building the capacity of lending officers in this important area. The ADF recently selected members for its new Sharia Board, which will certify the compliance of financial products and loan agreements with Islamic principles.

These innovations have been crucial to expand the portfolio of the ADF, especially considering that more than 40 percent of the portfolio consists of Islamic financial products. Innovations like these have made the ACE program one of the most effective U.S. foreign assistance initiatives in Afghanistan.