DEVELOPMENTS

Herat Economic Corridor Could Catalyze Growth in Western Afghanistan

Aug 27, 2014

Doing business in Afghanistan is tough. The last 30 years of conflict aside, private-sector growth is obstructed by perpetual mistrust, poor transportation and energy infrastructure, a lack of market information, and a business disabling environment. Infrastructure has been destroyed, investment discouraged, and industrial capacity depleted. Many professionals have left the country, while labor forces have been displaced or are untrained.

Well-meaning observers quick to cite the strategic advantages Afghanistan has in natural resources and transit potential also concede that the security situation might get worse before it gets better, further putting off investment and development needed to achieve this potential. Nowhere is the dichotomy between the current situation and future potential felt more acutely than in western Afghanistan and its provincial capital of Herat.

Herat’s ability to buck the trend looks promising on paper: Its economy is not as distorted by the “donor economy” as Kabul, and, as such, will be more resilient should a decline in donor-funded activities occur. Herat has good linkages to global markets—through Turkmenistan by rail to Europe, and through Iran by road to Europe and by sea to Dubai and beyond. Herat also has a privately owned and operated industrial park with dozens of enterprises producing products ranging from cut marble and spun cashmere to soda pop and potato chips.

Herat’s reform-minded Afghan-Canadian governor continues to strengthen the capacity of provincial government, earning confidence from a skeptical populace, and a recent international upgrading of the airport is set to carry entrepreneurs and high-value cargo to and from Dubai, Istanbul, and Delhi. Herat City enjoys a relatively good physical infrastructure, including 24-hour electricity and well maintained roads, and the city’s business community has decent access to finance, a well educated population, exposure to neighboring countries, and a tradition in trading. These factors have resulted in the rapid and expanding development of small and medium-sized enterprises in the surrounding area.

Further afield, Afghanistan’s western region (Herat, Badghis, Farah, and Ghor provinces) hosts a number of traditional industries, agriculture, and an established tradition in trans-shipment of goods. Though formerly dominant industries such as textiles, cement, and flour have fallen into disrepair, emerging industries such as saffron and marble offer significant opportunities. However, despite generally good security throughout the region, which makes it generally permissible for travel and project implementation, much of the region’s economic activity is centered in and around Herat City.

The Difference A Road Could Make

Despite enjoying a similar level of security and close proximity to this industrial hub, the rural districts of Herat remain significantly removed from this economy due to their lack of infrastructure, particularly the lack of an all-weather road connecting the region to Herat City. The absence of an improved road is increasingly cited as a major bottleneck in connecting the rich agricultural and mineral producing areas to the east with processing capacity and markets in Herat City. As a result, the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (GIRoA) has made the construction of an all-weather road between Herat City and the producing areas to the east a top priority.

The development of the Herat Corridor has been part of the Ministry of Public Works’ road network strategy for years, but only recently received complementary attention from the Ministries of Transport, Mines, and Agriculture, as it will also support their goals. In the second half of 2011, a Turkish team completed surveying 50 percent of the corridor and started on the remainder. GIRoA has committed $40 million for grading and paving the road, and the Italian Provincial Reconstruction Team has committed to fund up to half of the length of the corridor, with support from other donors firming up.

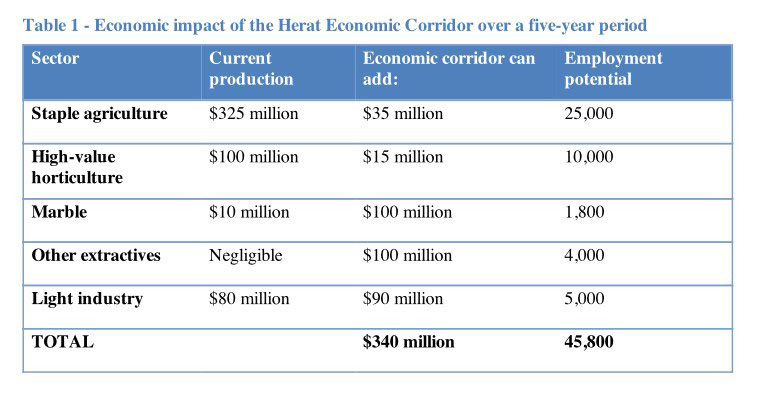

The two industries poised to contribute the most to economic growth are extractives and agribusiness. Extractives can contribute significant value in production and processing, but take time to develop, require large investment, and are highly mechanized and thus do not generate much direct employment. Agriculture involves a greater proportion of the population, is more inclusive, develops value chains for value-added processing, strengthens Afghanistan’s export profile, and contributes to national and regional food security.

In recent years, programs like the U.S. Agency for International Development’s (USAID) Afghanistan Small and Medium Enterprise Development (ASMED), implemented by DAI, have provided dozens of grants to firms that demonstrated the most potential for growth in many sectors, particularly in agribusiness and minerals. While a formal impact evaluation has not yet been performed, USAID evaluations found that similar programs in Iraq were highly sustainable in terms of jumpstarting a region’s economy and creating jobs.

However, sometimes these forms of assistance aren’t enough in effecting a catalytic impact. If lead firms cannot expand due to a lack of raw materials or lack of access to markets, the capacity of their added investment lies idle. Frequently, these firms need, and benefit significantly from, improvements in infrastructure and market linkages between producers, processers, and markets.

Connecting The Dots

Probably the oldest trade corridor still in use in one form or another is the Silk Road from China to Europe—the Herat Economic Corridor is part of it. Today’s economic corridors are meant to attract investment and generate economic activities, usually with the aim toward trade-led development. They are meant to provide two fundamental attributes for development: lower distribution costs and improved supply factors for economic activities. However, physical links and logistics facilitation must be in place for them to achieve these goals.

A basic principle of value chain development is linking markets with producers and other value chain actors. These linkages need to be based on information, commercial patterns, and transport infrastructure. The lack of linkages between the rural producing areas and Herat was recognized by the lead donors in the region such as Italy, the United States, Japan, and the Asian Development Bank.

But the Afghan government, private sector, and development community did not have a clear idea of the economic benefit of improving the road transport network, nor did they know what competitiveness impact an improved road would have on the existing products and commodities produced along the road.

They also needed to know how investment in supporting services and infrastructure would affect the competitiveness of the economic corridor. Support for the road investment was evident, but a justification and strategy was missing. A study commissioned by the DAI-led ASMED project provides some of that justification.

Potential Job Creation

Despite the high costs of construction and maintenance, the road offers many benefits to the development of a vibrant, diversified, and inclusive private sector in Herat and along the corridor. Possibly the most tangible is that farmers would have access to the large market of Herat City. Given the steady demand for raw materials and agricultural goods in Herat and beyond, integrating the producing areas to the east with the Herat market and processing facilities is critical to generating economic growth, improving livelihoods, and maintaining security in the region.

In addition to the benefits of value chain integration and transport improvements, a significant impact will be in employment generation. Road construction projects provide excellent short-term jobs for both unskilled and semi-skilled labor, typically sourced from the areas through which the road is built. Based on the construction of similar roads in Afghanistan, construction of the first 200 kilometers of the Herat Economic Corridor would require more than 2,100 workers for at least 18 months, injecting significant resources into the local economy and developing the local workforce.

Though precise long-term job creation and poverty reduction benefits are difficult to define, a significant number of additional full-time equivalent jobs would be created due to reduced transit times and costs, and increases in yields and productivity. For example, mineral mining and processing enterprises in Herat remark that with improvement of the road, the white marble industry alone could potentially generate several thousand jobs in transport, mining, and cutting/polishing. Other unexploited mines (gold and other minerals) exist along the road, each of which would benefit by improved transport efficiency.

The greatest potential for job creation is in agriculture. With more that 100,000 people living near the proposed corridor, the road will provide farm-to-market access for 200,000 acres of agricultural land that would also benefit from irrigation and the 47 megawatts of electricity for homes, processing equipment, and cold storage generated by the soon-to-be-completed Salma Dam. Most immediately, existing farm families would benefit from increased access to the Herat market, and with complementary planned extension services, training, market information, and investment, there is potential for tens of thousands of new jobs—on-farm, input supply, storage, transport, and food processing.

The road’s impact on farmers’ ability to access larger markets will have wide-reaching benefit in terms of reducing poverty, improving rural livelihoods, stemming urban migration, and improving food security. For agricultural goods, transport time and costs are expected to decrease by 75 percent. Farmers will also be able to more easily engage with Herat’s traders to gain a better understanding of demand and prices in the market.

Accessing a larger market with significantly lower transport costs will create many opportunities for farmers to increase production, diversify their crops, and hopefully engage in value-added processing—if the right mix of support and training is provided to assist them in leveraging this opportunity.

A Herat Economic Corridor could trigger Herat City into becoming an outward-looking regional industrial and trade hub. Could Herat become Afghanistan’s Chicago or Shanghai? The right fundamentals would appear to be in place, as long as the security and governance situation remains stable.